Marine and coastal habitats, including those key to storing carbon, have been damaged or completely destroyed, as the impact of climate change and industrial fishing hits Scotland’s seas.

Climate change is the “most critical factor” with impacts already showing, according to the latest Scottish Government study, while damage caused by fishing gear and pollution is also to blame. Rising sea levels in all Scottish marine regions, most notably at Stornoway, Kinlochbervie and Lerwick, are increasing coastal flooding and erosion risks.

As part of The Ferret’s Scotland’s Seas in Danger series, we studied the latest reports and other resources to reveal which marine and coastal habitats are deteriorating, which are most vulnerable or at risk, and why these ecosystems are so important.

No areas of seafloor around Scotland are now deemed to have ‘good’ ecological status, with many habitats that support hundreds of species harmed or lost.

Nine out of 21 marine regions had seafloor habitats predicted to be in poor condition across more than half of their area, according to the Scottish Government’s 2020 Marine Assessment.

Fishing, and particularly bottom trawling, which involves towing a net along the ocean floor, had impacted the most areas. Fishing gear affected at least 15 per cent of the seabed in all marine areas and seven of the 10 offshore marine regions.

Rising temperatures will be “particularly profound” for exposed, low-lying dune-wetland habitats such as those in the Outer Hebrides, the report warned, while oxygen depletion and ocean warming will make some habitats no longer viable for certain species.

Conservation bodies and coastal community representatives said the assessments made clear the “poor condition” of Scotland’s seabed, which they argued must be protected from damaging bottom-towed fishing gear to ensure a viable future for commercial fishing.

The Scottish Government stressed that safeguarding measures must not impact the livelihoods of coastal communities. It wants to support local groups looking to protect their marine environment.

Failures to protect habitats

In 2020, we discovered that Scotland had failed to meet a ten-year target to prevent damage to precious marine wildlife, according to a leaked Scottish Government report. It blamed the declines on dredging, trawling, anchoring, overfishing, engineering works, climate change, ocean acidification, fish farm pollution, diseases and storms.

Assessments showed some seabed habitats declined between 2011 and 2018, with seagrass, flame shells, seaweed beds, mussel beds and tubeworm reefs destroyed by the fishing industry and pollution.

Flame shells are molluscs which build nests from shells, stones and other materials, providing a habitat for other marine life. One study at Argyll’s Loch Fyne found that six nest complexes supported nearly 300 species, according to NatureScot.

But they are being harmed by trawling, dredging and poor water quality. Damage caused by fishing activity to a bed in Loch Carron, Wester Ross, in 2017 resulted in the creation of an emergency marine protected area (MPA), and flame shell beds are now protected in six locations.

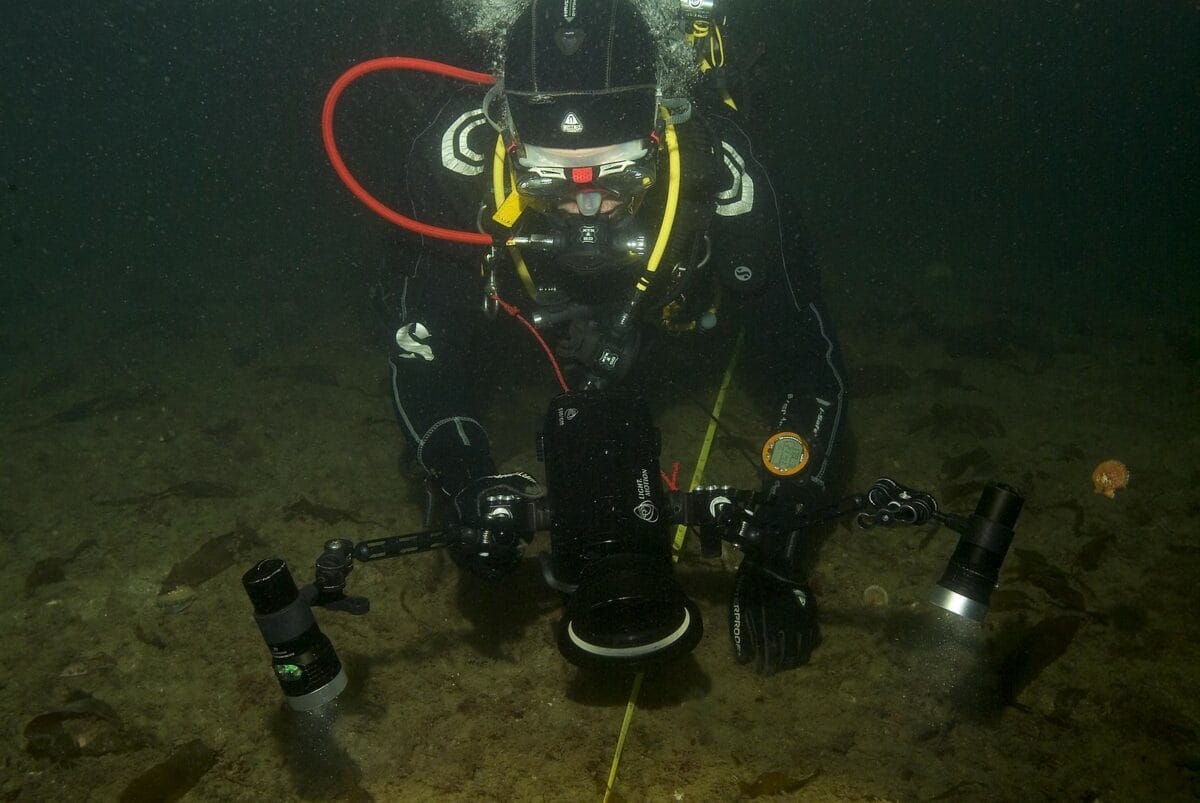

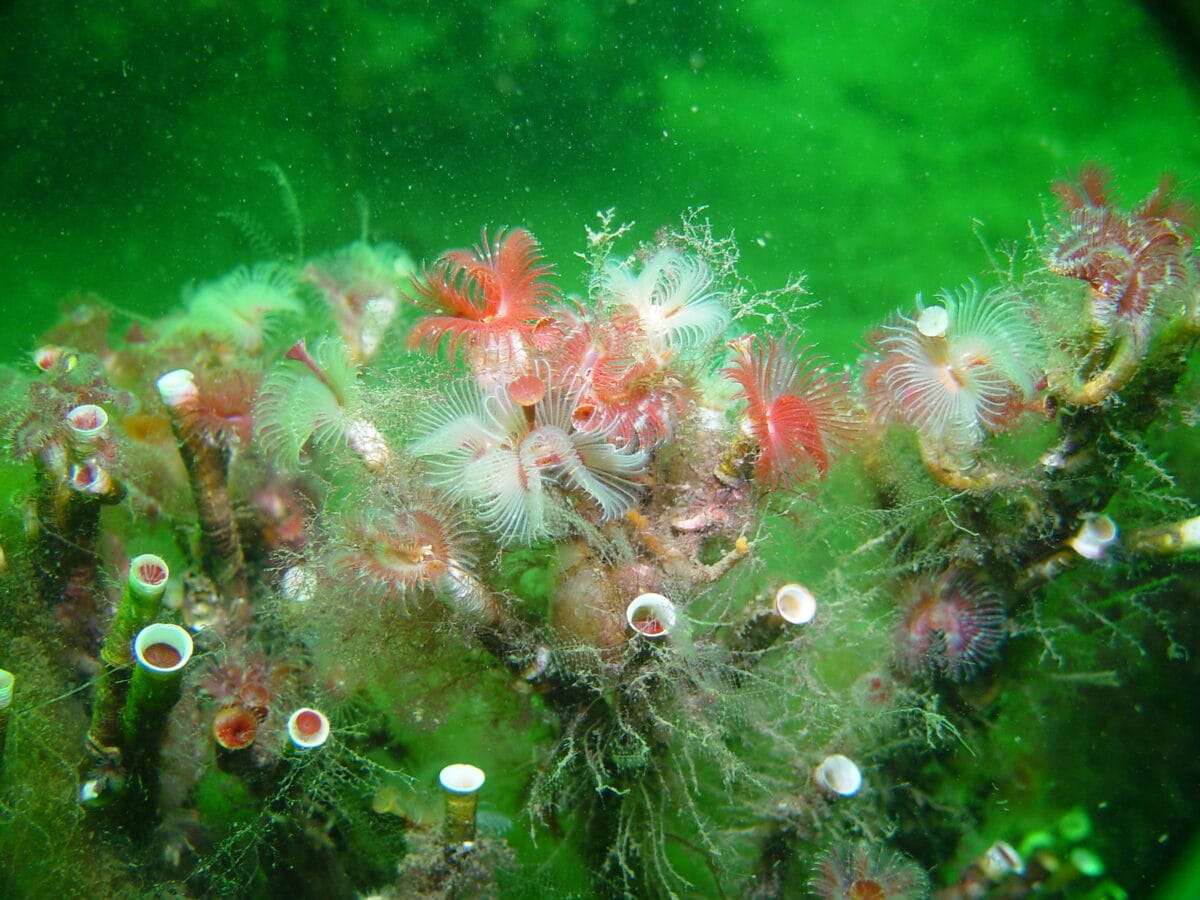

Serpulid tubeworms create reefs which house other animals such as sea sponges, crabs, lobster and starfish. They are “extremely vulnerable” to mobile and static fishing gear, anchors and mooring chains, fins used by divers, water quality and changes in water flow.

The world’s largest area of serpulid reefs are in Loch Creran in Argyll. But damage caused by suspected dredging was found in 1998. The loch became a protected area in 2005, but a 2019 assessment showed “little recovery” after 17 years, and experts are unsure whether reefs ever will, according to Marine Scotland.

Horse mussels beds provide the basis for soft corals, sea worms, barnacles, seaweeds and others, and habitats for animals including crustaceans, and shellfish, such as scallops. Bottom trawling has caused “widespread and long-lasting damage” to horse mussel beds, which are now protected in 12 locations.

Blue carbon stores

Horse mussel beds and other biogenic habitats – formed by key animal or algal species – are so-called ‘blue carbon’ stores, in which carbon is captured from the marine environment and locked up.

The protection of such habitats is “critical”, according to the marine assessment. However, the Scottish Government does not know how they might be impacted in the future. Seaweed beds, salt marshes and seagrass beds are also considered blue carbon habitats.

Kelp beds are described by NatureScot as “dense underwater forests, which are among the most productive and dynamic ecosystems on Earth”. They provide food and shelter for marine animals, and support food chains, including commercially caught fish.

According to the Scottish Blue Carbon Forum (SBCF), kelp supports over 1,800 species and protects coasts against waves. Carbon stored in kelp is swept away and may become buried in seafloor sediments which, along with sea loch sediment, store most of Scotland’s blue carbon.

Mechanical harvesting can damage kelp beds, although hand harvesting is predominant in Scotland, according to NatureScot. Mechanical trawling or dredging for kelp requires a licence from Marine Scotland, but none have been granted to date following an effective ban in 2018. Kelp beds are also protected in 17 locations.

Seagrasses shelter marine life, and act as nursery areas for commercially-caught fish like plaice and flounder, as well as pipefish – a relative of the seahorse – and rare native oysters, which produce reefs that in turn provide shelter and breeding grounds for other species.

Seagrass also makes Scotland’s coastline more resilient to climate change and erosion by stabilising sediments and reducing wave impact, according to the SBCF.

Seagrass beds are threatened by dredging, coastal development, invasive species and pollution with high levels of nitrates, such as wastewater or farm water run-off. They are protected in 26 locations around Scotland via MPAs.

Maerl beds – spiky underwater ‘carpets’ of purple-pink hard seaweed – provide key habitats for scallops, sea cucumbers, marine worms and others. They can be damaged by fish farms, dredging, anchors and mooring chains, and are expected to be harmed by rising temperatures and ocean acidification. Maerl beds are protected in 11 locations.

Saltmarshes can be found on most Scottish coasts, where the tide covers plants twice daily. According to NatureScot, Scotland has 7,076 hectares of saltmarsh with by far the largest areas found along Dumfriesshire’s Solway Firth.

Some 77 per cent of salt marshes lie within Sites of Special Scientific Interest. The habitats store vast amounts of carbon, help protect coasts from flooding, and are home to various species.

Other notable marine habitats include cold-water reefs, sea lochs, burrowed mud – which shelters lobsters and other animals – and North Sea fan and sponge communities, which break down waste and detoxify the surrounding water and sediments, according to NatureScot.

Many of these habitats are also threatened by climate change, pollution, fish farming, fishing activity, oil and mineral exploitation, the laying of cables and pipelines, and other pressures.

Protecting marine habitats

Calum Duncan, head of Scotland at the Marine Conservation Society, claimed the Scottish Government’s 2020 marine assessment “makes clear that the poor condition of the seabed is one of the main environmental concerns in our seas”.

“We therefore urgently need the long-awaited measures to safeguard the rest of our network from the most damaging forms of fishing that sweep heavy gear across vulnerable seabed habitats,” he said.

Vulnerable habitats outwith MPAs must also be shielded, while the planning and management of fisheries needs to “actively support the recovery of nature throughout our seas,” added Duncan.

John Aitchison from the Coastal Communities Network, which is made up of 24 local groups across Scotland, said the Scottish Government’s National Marine Plan had “failed” to protect biogenic reefs. “This is inexcusable,” he said, and called for a new plan that is “fit for purpose, followed by real action from the government”.

Bottom trawling had “profoundly changed” seabed habitats, he added. “If those habitats are also nurseries for commercial species, then we all lose, in particular people in coastal communities who make a living from catching those species.”

Màiri McAllan, the Scottish Government’s net zero and just transition secretary, said protection measures were “vital for the viability of our marine industries”. But they must be delivered in a “fair” way and ensure seas remain “a source of prosperity for the nation, especially in our coastal and island communities”, she stressed.

Work on proposed measures to manage fisheries for MPAs, and to protect priority marine features (PMFs), which include habitats and species, “has been underway for several years and involved many engagements with stakeholders,” McAllan added.

“We also remain willing to support local groups that wish to pursue community-led marine protection in their local area. It is crucial that people who will be affected by policies are engaged in their development.”

NatureScot said there was “relatively good evidence” of the state of coastal habitats. But information on habitats beyond the shoreline – including those important to biodiversity and blue carbon – was “more limited”.

A spokesperson added: “Our view is that the main focus should be on reducing pressures on marine habitats, including through the use of nature-based solutions and continuing conservation measures for MPAs and PMFs.”

Scotland’s Seas in Danger is a year-long investigative series by The Ferret that delves into Scotland’s marine environment. Our investigations were carried out with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

This project is was conducted in partnership with the Investigative Reporting Project Italy (IRPI), which will publish its work later this year.

If you like what we do and want to help us do more independent journalism, you can support us by becoming a member. You can also donate or subscribe to our free newsletter.

Main image: NatureScot