The UK government has failed to meet its official criteria for conducting “regular and thorough inspections” of arms facilities every three years at a controversial bomb factory in Scotland, The Ferret and Declassified have found.

It follows revelations of missed inspections at a fighter jet factory in England, raising concerns about systemic failings by government weapon inspectors, who have now admitted to four separate lapses across Britain.

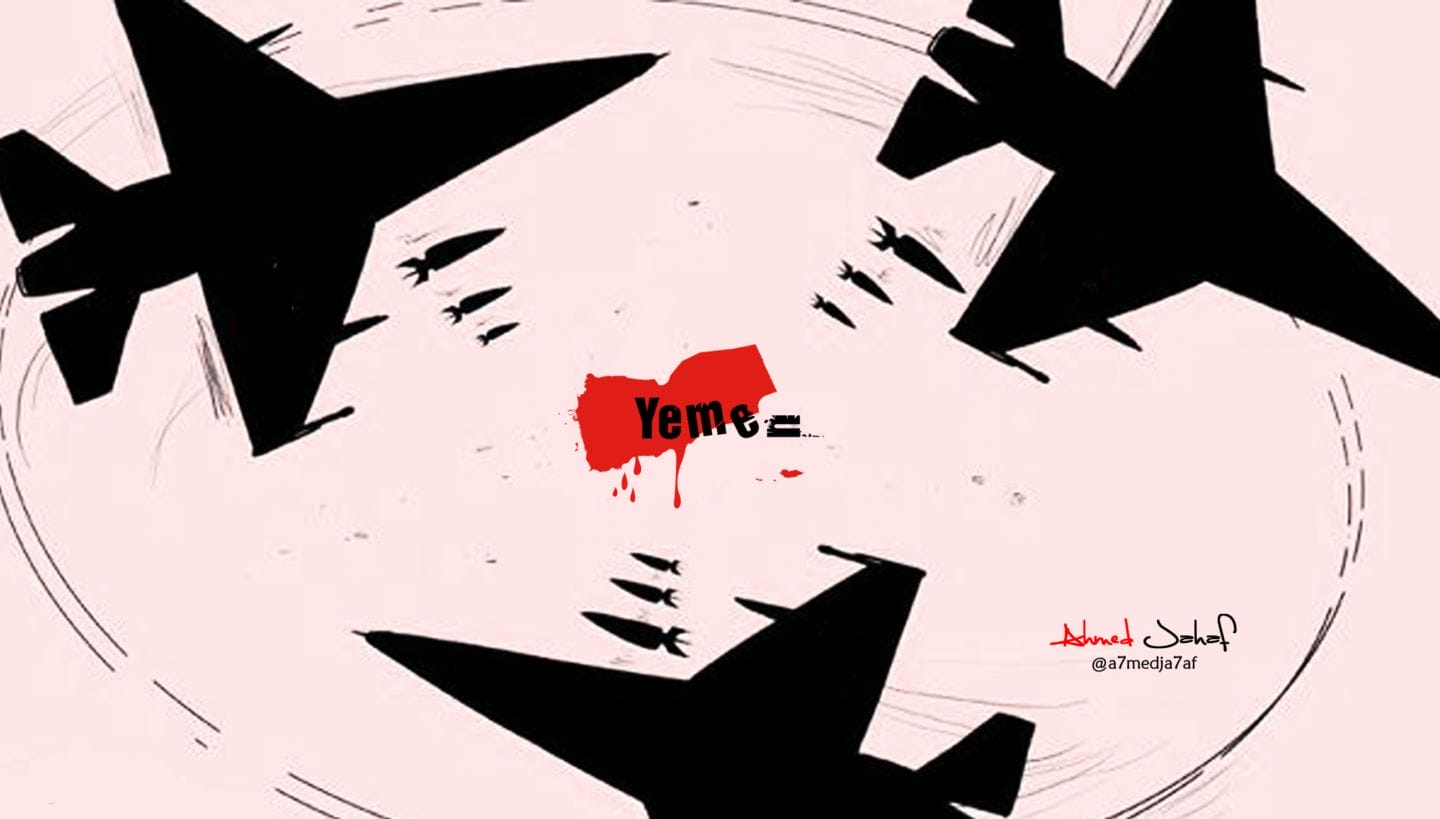

US arms giant Raytheon’s missile factory in Glenrothes, Fife, has not been inspected since November 2016. The site makes parts for the company’s Paveway IV missiles supplied to Saudi Arabia, which human rights groups believe are directly linked to war crimes in Yemen.

Inspections are a safeguard designed to ensure British-based arms exporters abide by government regulations, but their lack of frequency undermines repeated claims by ministers that the UK operates “one of the most robust export control processes in the world”.

The full scale of missed inspections remains unclear because UK trade minister, Ranil Jayawardena, told Parliament that identifying all lapses would involve a “disproportionate cost” to manually review all of his department’s records. He also refused to tell MPs the outcome of the inspections that have been completed, claiming the results were “commercially sensitive”.

However, when asked specifically about eight of Britain’s most controversial weapons factories – all connected to Saudi Arabia’s bombing of Yemen – Jayawardena admitted that half of them had not been visited by inspectors for more than three years ago, in breach of his department’s own rules.

One site, run by Raytheon, has not been inspected in nearly five years – almost the entirety of the Yemen conflict. Raytheon’s UK operation is chaired by Conservative peer, Lord Strathclyde.

Raytheon’s smart bombs linked to more alleged war crimes in Yemen

Andrew Smith, spokesperson for Campaign Against Arms Trade, said: “These sites have been crucial in terms of producing arms for the Saudi-led bombing campaign. The fact that the government appears to be failing in its own obligations raises serious questions about the scrutiny being applied and the cosy and compromising relationship between arms companies and government.”

Smith added: “This does not look like a case of one mistake – it looks like a systematic failure. Why has this kept happening, and, just as importantly, what is being done to ensure that it never does again?”

The Scottish Government stressed that it “expects inspection regimes to be adhered to and has consistently called on the UK government to end its flawed foreign policy approach.”

A spokesperson added: “The Scottish government has repeatedly made very clear that, whilst this is a reserved matter, the UK government must properly police the export of arms and investigate whenever concerns are raised.”

Typhoon fighter jet factories run by BAE Systems, Britain’s largest arms corporation, at Warton and Samlesbury in Lancashire, northwest England, have not been checked by government inspectors since April 2017.

Saudi Arabia has used its fleet of 72 Typhoons, many of which were made at these BAE factories, to repeatedly conduct airstrikes in Yemen throughout the last five years.

These strikes have continued during the coronavirus pandemic and in April a Covid-19 quarantine centre was bombed by the Saudi-led coalition, according to the Yemen Data Project.

Inspectors last visited Raytheon’s Paveway missile factories in Glenrothes, Fife, on 23 November 2016 and in Harlow, Essex, on 5 November 2015 – breaking the three-year minimum inspection guidelines.

‘Alleged war crime’

Saudi Arabia fired so many Paveway missiles in Yemen that three months after the war started in April 2015 the UK military agreed Raytheon could prioritise resupplying the Saudi air force ahead of the Royal Air Force (RAF), which also uses the missiles for operations in Iraq.

In 2016, a report by Human Rights Watch said that a code found on bomb debris in Yemen linked Raytheon’s Scottish operation to an alleged war crime. Remnants of a missile found after a chamber of commerce building was bombed in the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, were from a “Mk-82 500-lb bomb with a UK-manufactured Paveway laser guidance kit.”

Markings on the fragments showed that a Raytheon subcontractor produced the bomb in Scotland, at Kelso, south of Edinburgh.

In another incident, a Paveway IV missile produced in the UK in May 2015, was dropped on warehouses in an industrial area near Hodaida, Yemen’s major western port, on 6 January 2016, according to the Human Rights Watch report.

BAE and Raytheon were referred to the International Criminal Court in December 2019 by a coalition of human rights groups which accused the arms companies of being party to alleged war crimes in Yemen.

Douglas Chapman, Scottish National Party MP for Dunfermline and West Fife, and a member of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Yemen, said the infrequent inspections of Raytheon’s factories “highlights the reckless, irresponsible attitude of the UK government towards the conflict in Yemen.”

He added: “The UK government needs to start taking responsibility for its actions, because so far it has turned a blind eye to the pain and suffering its weapons are causing.”

Scottish Green external affairs spokesperson, Ross Greer MSP, said: “It’s clear but hardly surprising that we cannot rely on the UK government to police arms sales. Its claims to be building a ‘global Britain’ is nothing more than a smokescreen for protecting the profits of multi-billion pound international arms firms, regardless of the horrendous suffering it results in.”

Greer also criticised the Scottish government for subsidising the arms trade through the “huge handouts of public cash its enterprise agency gives to these same arms dealers.”

Although the Court of Appeal ruled in 2019 that UK ministers could not grant new export licences to Saudi Arabia for weapons that might be used in bombing Yemen, the government is allowed to continue exporting equipment under older licences.

Section 31 of the Export Control Order 2008 gives the Department for International Trade the power to conduct unannounced inspections of arms factories in the UK. UK trade minister, Ranil Jayawardena, told parliament “their purpose is to get assurance that users of general licences meet the terms and conditions of their licences.”

While the frequency of inspections varies according to several factors, the minister said they are supposed to happen every three years at a minimum. This deadline is repeated in the government’s strategic export controls annual report.

Once acquired, export licences allow companies such as BAE and Raytheon to send military equipment from the UK to their customers abroad. BAE runs a weekly Boeing 737 freighter flight from its Typhoon factory in Warton to a major Saudi air force base in Ta’if, from where bombing raids on Yemen take off.

The freighter flight is owned by Swedish firm West Atlantic but little is known about its cargo, which is kept secret even from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).

A freedom of information request to the CAA by Professor Anna Stavrianakis – an international relations expert at Sussex University – found that: “West Atlantic hold general approvals to transport dangerous goods, weapons of war and munitions of war.”

However the CAA was not able to provide any more detail, saying: “Approvals for UK operators are typically issued on a long term or non-expiring basis, and there is no requirement for an operator to advise the CAA of what it is transporting on any particular flight.”

Stavrianakis commented: “The inspections regime, such as it is, seems increasingly like part of the armoury of claims to benevolence, rather than any actual effort to implement robust controls.”

From August the CAA will be managed by Sir Stephen Hillier, the former head of the RAF from 2016 to 2019. In that time he oversaw UK military support for Saudi Arabia’s bombing of Yemen.

Dozens of RAF and other UK military personnel work closely with the Saudi air force, including through secondments to BAE Systems, under a scheme known as the Ministry of Defence Saudi Armed Forces Projects (MODSAP). Three UK military personnel are embedded in the Saudi Air Operations Center.

When Houthi rebels shot down a BAE-made Saudi Tornado jet over Yemen in February, MODSAP officials “did verbally discuss the possibility of offering technical assistance to the Royal Saudi Air Force with the investigation of the crash,” according to a freedom of information response.

However, no assistance was ultimately requested and MODSAP claims not to hold any written records about the incident.

A UK Government spokesperson said: “The UK assesses all export licence applications on a case-by-case basis in line with our strict licensing criteria. We will not issue any export licences for Saudi Arabia that are inconsistent with this criteria, including with respect to International Humanitarian Law.”

Raytheon and BAE Systems have been approached for comment.

Phil Miller is a staff reporter for Declassified UK, an investigative journalism organisation that covers Britain’s real role in the world.

Image © a7media7af

This story was updated at 07.44 on 19th June 2020 to add a comment from the UK Government.