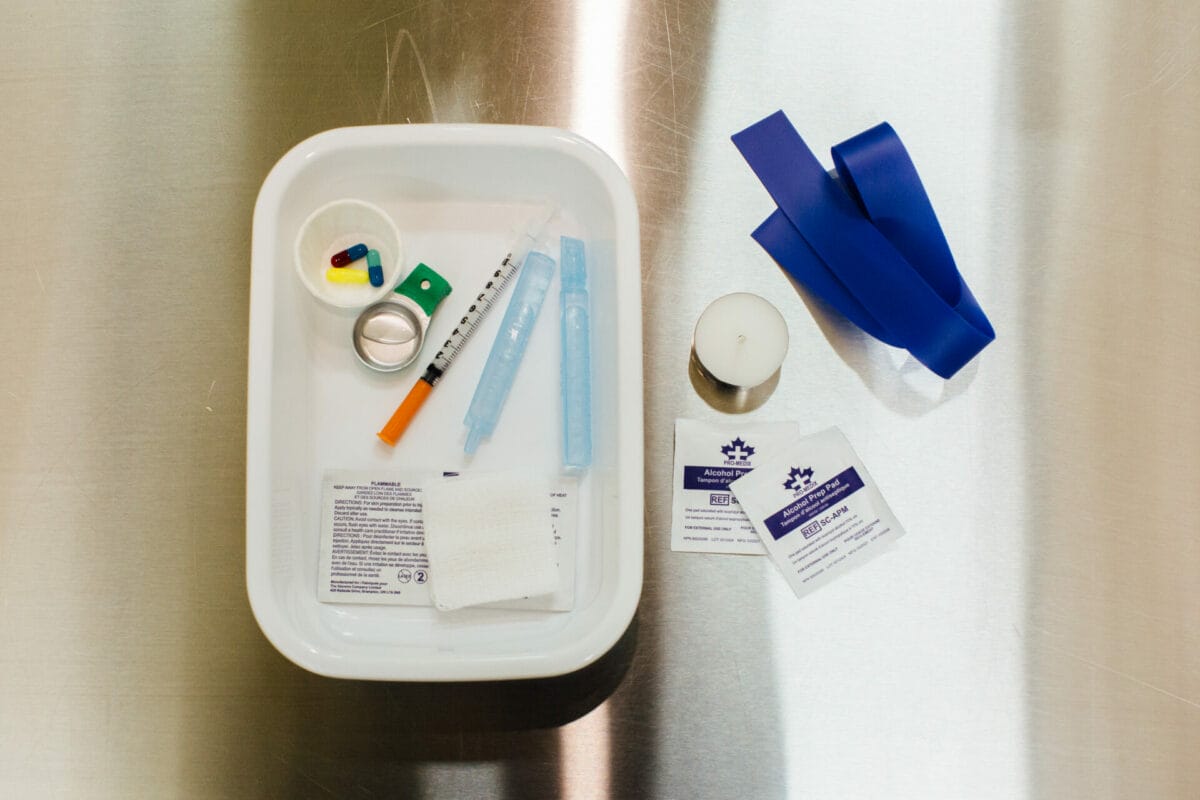

The morning sun begins to sweep slowly across the city of Vancouver as the traffic noise starts to build. In her midtown flat, with its views over the downtown skyline to the soft blue of the Canadian mountain ranges beyond, BeeLee takes a tiny vial of liquid hydromorphone – a synthetic opioid sold under the brand name dilaudid – and draws its contents into a syringe.

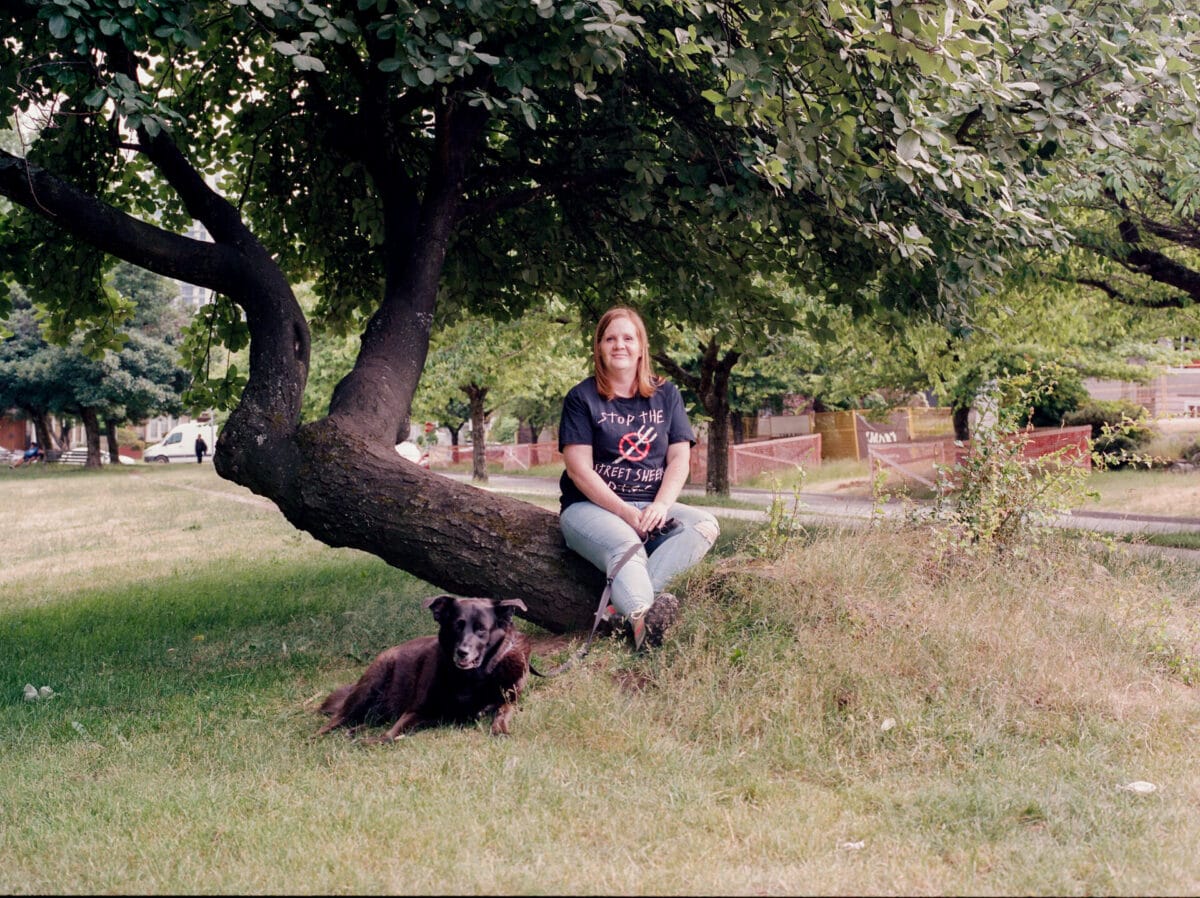

She injects it into her muscle, then it’s time to get on with the rest of her morning routine. She walks her dog, Sadie, and drives to work in the city’s downtown eastside, where she works for a harm reduction service.

BeeLee, now 48, was prescribed hydromorphone at the beginning of 2019 after many years of addiction to first prescription, and then illicit drugs. Three times a week she visits a nurse for her morning injection. For other days, and afternoon top-ups, she is given “carries” – supplies she is allowed to use at home without supervision. This is what is helping her find stability again and rebuild the life she wants to live, she says.

Since 2016, when BeeLee’s home province of British Columbia announced a public health emergency, 36,000 Canadians have died from toxic drug poisoning. Safer supply – which includes the prescription of medical grade heroin, diamorphine, and liquid or tablet form hydromorphone – is a response that aims to save lives.

While still limited, the number of safer supply programmes in Canada’s major cities has grown in recent years. One Vancouver-based programme, overseen by Dr Christy Sutherland, even prescribes fentanyl. Unlike traditional programmes, other drug use is not banned though most people are trying to stop or reduce it. Most also offer counselling services and support with housing, legal issues or referrals to other programmes.

In the UK, this type of approach was once relatively common – doctors prescribed heroin until the late 1960s, a treatment so normalised it was known as ‘the British system’. Now in Scotland this is only available through the enhanced drug treatment service in Glasgow, which has worked with about 30 of the most complex drug users in the city.

But in a new report published on Thursday 31 August – marking overdose awareness day – the Home Affairs Committee is demanding change. It made headlines by calling for drug law reforms to allow Glasgow to pilot a drug consumption space, where people can inject drugs under supervision.

But it also made a raft of other recommendations including that the UK Government provide funding for diamorphine treatment for people with a “chronic heroin dependency” where other treatment had not been successful.

“This drug situation is already at a crisis point,” says Niamh Eastwood, of drug campaigning organisation Release. She warns that with the recent rise in synthetic opioids in the UK things could get worse. “This is why the UK and devolved governments must take action and ensure that treatment services are encouraged and supported to respond to the crisis through the supply of substitution medications.”

In Canada, safer supply programmes were born in the midst of the drugs crisis. Like many places across the world, the country experienced a sharp increase in deaths from heroin in about 2010. But a few years later it was deaths from fentanyl – a man-made opioid that can be 50 times more potent than heroin – that started to increase with dizzying pace. Now the deaths include those fuelled by fentanyl, cut with everything from benzodiazepines to veterinary sedative xylazine, known as Tranq Dope.

During 2022, 7,328 people died from opioid overdose across Canada – 2,342 in British Columbia alone. The deaths have not slowed – in the first seven months of this year 1,455 British Columbians died as a result of the toxic drug supply. That’s almost seven a day in a province not much bigger than Scotland.

It’s led to calls for a radical change of tack from conservative politicians and their advocates, who claim harm reduction measures are the cause, not the cure for the escalating deaths.

Campaigns run by right wing lobbying organisations like the Pacific Prosperity Network – which also owns social media pages like BC Proud – have demanded Vancouver “say no more free drugs” and lambasted “so-called leaders who continue to promote the myth of ’safe supply’”.

They claim the programmes are being “abused” with prescription drugs resold on the street. But health authorities insist that this isn’t evidenced, and participants and doctors involved in safer supply programmes say this just isn’t the reality. In May, Conservative Party of Canada leader Pierre Poilievre failed to gain backing for a motion to defund the programmes and invest dollars saved into treatment centres.

For BeeLee her hydromorphone prescription is simply the only thing that has worked. Her drug use dates back to her teens when illicit substances were just for fun. But she acknowledges: “It got chaotic really fast. It was kind of problematic use – like binge using cocaine and alcohol.” Within months she was involved in a robbery as the getaway driver.

She married at 19 and both she and her husband stopped taking drugs when she had kids in her twenties. But as the couple fought to regulate her husband’s immigration status in Canada their relationship became strained. BeeLee, by this point a well-paid medical lab technician and raising two young children, was diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

In pain, she went to the doctor and was prescribed oxycontin, the prescription drug at the centre of the opioid crisis. “From the very first pill I was like ‘“oh wow’,” she remembers. “I just loved these pills. They took the pain away.”

She and her husband broke up. But her next boyfriend was also a cocaine user. When she told him she didn’t like cocaine, he persuaded her to try smoking heroin. And as their use increased – and the amount of money required along with it – they started injecting – “the absolute worst decision I ever made,” she says.

She lost her job and her kids went to her mother’s, and then to foster care. “My addiction was so strong that not even the love of my children could make me get well,” she says.

By now her boyfriend was selling her belongings in the streets of the downtown eastside for drug money and the couple ended up in a shelter there. BeeLee went to treatment centres but returned to drug use when there was no follow-up support. Now on her own, she started funding her drug use with occasional sex work and drug dealing. Her use escalated.

And then she finally got a break. “I was moved into the Budzey, which is like supported accommodation for women and families,” she says. “It was a new building with lots of services and good staff, a new programme. It was kind of like the sense of hope that maybe my life would get a little bit better.”

Within months she was working as a “peer worker” in an overdose prevention site and while there met others moving on with their lives with the help of safer supply. “At the time the heroin had dried up and I was dwindling away doing fentanyl because I had no choice,” she says. “It’s just so surprising that I didn’t die.”

So she went to the doctor and begged. Initially she was turned away. But the nurse who managed the programme intervened, she changed doctors and after a blip at the start, hasn’t looked back.

At work she was promoted rapidly and is now in a leadership role. She’s had counselling, started rebuilding relationships with her now grown-up kids, and campaigns for housing rights in the downtown eastside. Though she’ll always consider herself part of the east Vancouver community, since moving earlier this year she feels at peace. And almost everywhere she goes she’s accompanied by rescue dog Sadie with whom she feels happiest.

“This is the first time I’ve been so stable in many years,” she says. “If I had diabetes I would take insulin. This medication allows me to live and work and do all the things I want to do.” Now she believes she was always self-medicating. She’s going through diagnosis for attention deficit disorder(ADD) and is interested in the connection between drug use and mental health.

“The problem here is not ‘safe supply’,” she says. “That’s the scapegoat. The real issue is that people aren’t listening to those with experience to find the solutions.”

In Toronto, nurse practitioner Mish Waraksa agrees that’s where the focus should be. She’s the clinical lead for Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre’s safer opioid supply program, which prescribes hydromorphone tablets (brand name dilaudid) to about 140 people who can choose whether to take them orally or snort or inject. Most are also taking a traditional opioid replacement as well – like methadone – get counselling and other support.

It means they no longer have to spend their days finding ways of buying drugs or engage in risky behaviours from sex work to shoplifting, says Waraksa. “We see people’s lives improve tremendously. The majority of people that we see are people who have tried methadone or suboxone and other treatment forms for years and years and now they’re here, something’s working for them.”

But programmes like this are still few and far between and hugely over-subscribed. When it opened for new participants in February, it received 56 eligible applications for just 15 places.

Damien, is one of those who struggled to access a programme for years. When we meet he’s been on South Riverdale Community Health Centre’s safer supply programme for a month, combining 500 milligrams of Kadian a day with 24 Dilaudid tablets which he can use to control urges.

“It was about patience,” he says of the journey to get here. Previously he was using large quantities of fentanyl every day and laterally was overdosing once or twice a week. He’s alive, he says, because he was using in overdose prevention centres, where staff were on hand with oxygen and overdose reversal drug Naloxone, to bring him back.

Now, he says the changes are “amazing”. Instead of spending his days begging for drug money he’s at support groups and volunteering for harm reduction organisations. He’s got his dental care sorted, has a new family doctor in a city where that’s a tall order, he’s also put on 30 pounds and is sleeping for ten hours a night.

“And I don’t have to worry about overdosing anymore,” he says. “That’s the big thing. Very soon I hope to be totally drug-free with the exception of my prescriptions and eventually to taper off of that as well. Hopefully I’ll be working after that. I’d like to become a harm reduction worker, something in the field.”

In Canada the future of safer supply programmes is far from secure. The Ferret heard reports of people’s prescriptions being discontinued and of doctors and staff concerned about the threat of Conservative backlash to the future of their programmes.

But in Scotland, some advocates believe it’s an approach we should learn from. “We have retreated so far from the notion of safe supply,” Kirsten Horsburgh, chief executive of the Scottish Drug Forum said of the UK’s approach.

Medical grade heroin, benzodiazepines and even stimulants could all be prescribed to stop people relying on dangerous street versions, she claimed.

“It would be possible to provide a safe supply to replace the street drugs that are killing people. Progress towards this is so slow that almost nothing happens from one year to the next. It’s not unusual to have doctors, who would be relied upon to lead this, talking about how it would take someone who was brave to start this work.

“But it’s not brave to follow evidence and common sense,” she says. “It’s reckless not to.”

Images: Jackie Dives

This story was published in partnership with the Sunday Post. Our partnerships with other media help us reach new audiences and become more sustainable as a media co-op. Join us to read all our stories and tell us what we should investigate next.

This article is part of our Mind the Health Gap project, funded by the European Journalism Centre, through the Solutions Journalism Accelerator – a fund supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.