On the morning of June 28, 2023, a small village in the Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast of Ukraine awoke and began to prepare for a visitor. Though having never been to the town before, he had a long history with the place – an obsession fuelled by a promise to complete a journey 80 years in the making.

After a lengthy three-day drive from Edinburgh, a convoy of 25 Jeeps and more than 60 alternating drivers arrived in the town square to cheers from a 100-strong crowd of people. One by one, the 4x4s came, mounting the pavements and clearing a path for the final vehicle. As an old Ford Maverick slowly rolled to a stop at the head of the column, the visitor stepped out.

As he approached, a woman in her eighties, draped in a green babushka platok (granny’s shawl), emerged from the crowd and she began weeping as the visitor embraced her.

The man is Iwan Tukalo, and this was his long-estranged aunt, Paraska. He had finally come home. For those invested in Scottish rugby, Tukalo needs no introduction. He is often considered one of the greatest players of his generation. In 1990, with him gliding along the wing, Scotland beat England 13-7 to win a historic Five Nations Grand Slam, and a legacy to last a lifetime. However, with his glittering rugby career behind him, Tukalo set himself a new goal with a more personal motivation.

With the aid of the charity Jeeps for Peace, Tukalo committed himself to an almost 2,000-mile journey across Europe with the aim of helping the people of Ukraine. A second-generation Ukrainian immigrant, Tukalo says he always had a strong affiliation with the home country he had never visited.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Tukalo committed himself to helping his country in any way he could. Nearly 18 months after the beginning of the conflict, he came across the Scottish charity, which had already helped bring over 50 4x4s filled with food and medical aid into Ukraine. During an interview, Tukalo recalled his decision to get involved:

“I remember calling Stewart ,” he said. “We must have spent hours speaking on the phone. I told him I was interested in helping the charity in any way I could – that I’d even help get the jeeps to Ukraine.”

Tukalo went on to describe his ‘penny drop’ moment: “Stewart asked me where my Ukrainian family came from. I told him it was a small town in the southwest called Nyzhniv. There was a long pause on the phone after I said that. When I asked what was wrong, Stewart said: ‘Our convoys go past Nyzhniv on their way to Kolomya.’ I was stunned. I knew in that one moment that I was going to complete my father’s dream. Being able to finally go home.”

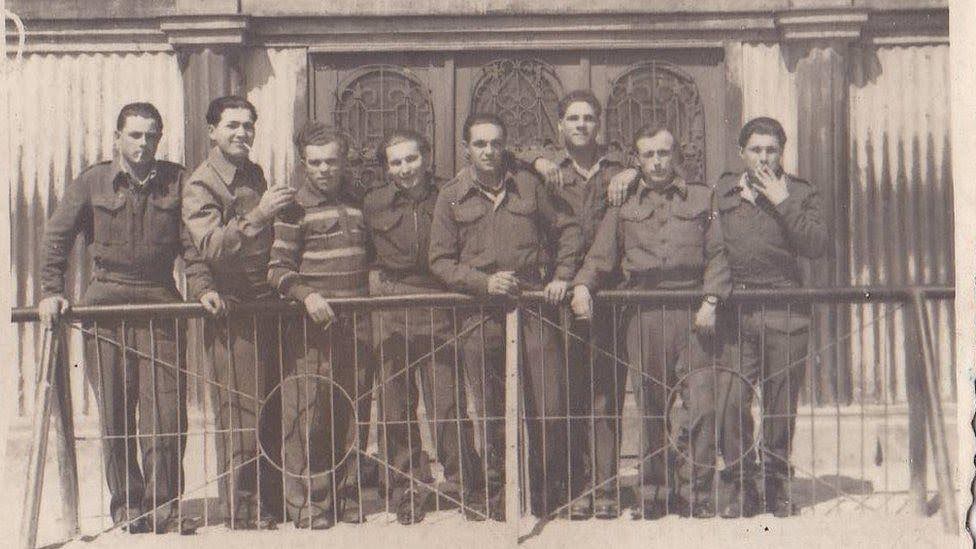

Dmytro, Tukalo’s father, was only 18 when he last saw Nyzhniv. After Germany invaded the USSR in 1941, Ukraine quickly became one of the war’s deadliest battlegrounds. With his town occupied by the Germans, Dmytro was caught up in the controversial 1st Galicia Division – siding with the Nazi invaders against the Soviets.

By 1945, the tide of war had firmly turned against Germany. Dmytro, stationed in Austria with the Galicia Division, faced two options: surrender to the Soviets and face near-certain retribution for supporting the Nazis, or surrender to the British. With a roughly 35.8 per cent chance of dying in a Russian prisoner of war (POW) camp, Dmytro, with the rest of his division, travelled south to surrender to British forces.

He spent the next two years in a British POW camp in Italy until he and 500 others were shipped to a new camp in East Lothian, Scotland. Upon his release one year later, Dmytro was granted British citizenship and settled in Edinburgh. He never returned to Ukraine.

“My father,” Tukalo explained while trying to compose himself, “always dreamed of returning to his hometown… even until his death, he still wanted to go back… I’m so happy I could complete his journey for him.”

Tukalo approached some of his fellow former Scottish rugby stars, asking them if they would like to accompany him on his aid mission to Ukraine. Ex-players Finlay Calder, Colin Deans and Gordon Hunter all agreed without hesitation, with Hunter even donating his 4×4 to the charity. “I’ve known Tuks (Tukalo) for almost 40 years,” said Hunter. “I’d do anything to help him make it there.”

After leaving Edinburgh and criss-crossing through five countries in three days, an exhausted but determined convoy reached its last stop-off point before Kolomyya – the small town of Nyzhniv. At long last, nearly eight decades after his father said goodbye to his family and went to war, Tukalo was finally reunited with them.

Calder described it as “a moment that will stick with me forever”. He added: The two most important aspects to the Ukrainian people are their country and their families. I feel so honoured to be here helping both”.

The mayor of Nyzhniv, accompanied by the town’s Orthodox priests, also welcomed Tukalo and the rest of the convoy. After personally thanking Tukalo for his efforts, the mayor turned to address the rest of the group.

“God bless you all and all of your families,” he said. “You all put your lives on the line for us. We all appreciate it so much. Thank you for everything.”

Tukalo, his relatives, and other volunteers then began a tour of the town. Tukalo saw the church Dmytro would have attended, along with the graves of family members, many of whom had recently passed away.

Edinburgh-born Tukalo was taken to his family’s home for a meal. Later, when passing by the schoolhouse, his aunt stopped to share a story. “The Germans,” she told a translator, “took your father and all other boys his age to that schoolhouse. They told him that he would fight the Russians, and if he didn’t, they would shoot him… this was the last place he was before they took him away.” Paraska, and the townsfolk of Nhzhniv, said many other boys Dymtro’s age, were forcibly conscripted under the threat of death.

The Galicia division has been surrounded by controversy, with the consensus for years being they were a volunteer force responsible for many atrocities throughout the war. Only recently has historiography shifted to consider views like those in Nyzhniv. Historians including Olesya Khromeychuk highlight that modern politics have dictated the historical landscape of Ukraine for decades, with the “historical truth” unclear. While it is not known what actions Dmytro took during the war, it is clear he was swept up in something larger than himself – not of his choosing – and never saw his home again.

As the time approached for the convoy to leave, the town’s orthodox priests showered the jeeps and their drivers with holy water, and gave them a blessing to protect them from harm.

Again, a member of the Tukalo family would be leaving the village that had been their ancestral home for generations. “I will return here again,” promised Tukalo. “My work in Ukraine and in this village will never go away.”

As he said goodbye to his family, Tukalo grabbed a jar from the back of his pickup and began filling it with soil from a nearby spot of grass. “If my father can’t make it back to Ukraine, I’ll take a bit of Ukraine back to him,” explained Tukalo, who said he intended to place the soil at his father’s grave, and help him complete his journey home.