The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, angrily rejected a proposal from her Foreign Secretary, Douglas Hurd, for £1 million to help the African National Congress (ANC) three months after Nelson Mandela was released from prison.

Handwritten comments on documents newly released by the National Archives show that in May 1990 Thatcher thought that the ANC was “still committed to armed violence”. She wrote in capitals: “WE DO NOT FINANCE violence”.

This was despite funding through the United Nations (UN) being recommended by Hurd and backed by the South African’s then apartheid government under President FW de Klerk, as well as Mandela’s ANC.

The funding was to help 25,000 ANC exiles return home to South Africa as the apartheid regime was dismantled. The regime enforced racial segregation and systematically discriminated against the majority population in favour of white South Africans.

The system was resisted by the ANC, in which Nelson Mandela was a senior figure. After police killed 69 unarmed people in Sharpeville, the ANC was banned and in 1963 Mandela was convicted of sabotage and sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island.

But after decades of international criticism, boycotts and sanctions, the racist regime began to collapse. In February 1990 De Klerk released Mandela and began negotiating the end of apartheid.

On his release from prison on 11 February 1990, Mandela said that the armed struggle, begun in 1960 as a “purely defensive action” against apartheid violence, had to continue. “We express the hope that a climate conducive to a negotiated settlement would be created soon so that there may no longer be the need for the armed struggle,” he added.

On 29 May 1990, Hurd wrote to Thatcher. He proposed that the UK government contributed £1m over two years out of “existing allocations” towards a repatriation scheme administered by the UN refugee agency, UNHCR.

The scheme aimed to help South Africans who had fled apartheid to camps in Zambia, Tanzania and elsewhere to come home by financing their transport, food and shelter. “It is clear that the international community will have an important role to play,” said Hurd.

“There can of course be no question of contributing funds directly to the ANC nor even to a trust set up by them to aid the return of exiles. Ideally the money should be channelled through an international agency which would operate on a non-discriminatory basis.”

Thatcher’s handwritten comments on Hurd’s letter show her anger at his proposal. “NO,” she wrote in notes meant for her private secretary, Charles Powell. “We don’t finance violence ever.”

She added: “The ANC have been generously financed for violence by the Communists. I see NO reason to give them money. They are still committed to armed violence. WE DO NOT FINANCE violence.”

Andrew Feinstein, a South African journalist and former ANC member of parliament, condemned Thatcher’s stance. “The Thatcher government were committed supporters of apartheid South Africa with whom they cooperated on arms and oil deals as well as other sanctions-busting initiatives,” he told The Ferret.

“The effort to move, house, feed and generally look after all the returning exiles was massive. But, it would appear, it was insufficient to overcome the hatred from Thatcher towards the ANC.”

John Nelson, a Hamilton campaigner against apartheid and secretary of Action for South Africa Scotland, described Thatcher as one of the chief protectors of the apartheid government. “She never really felt the revulsion against apartheid felt by most normal people,” he said.

“She never acknowledged the sheer enormity of it, and so always opposed any kind of action against it. To oppose any support for the agreed return of exiles as part of the long and painful process to bring about a negotiated non-racial and peaceful future for South Africa was really quite pathetic.”

Labour MP Paul Blomfield, a member of the Anti-Apartheid Movement’s national executive committee from 1978 to 1994, argued that Thatcher wasn’t alone. “There were many in her party who eulogised Nelson Mandela later, but they condemned him as a terrorist when he needed their support,” he said.

“Thatcher’s government stood in the way of change in South Africa for too long, using their veto at the UN Security Council to prevent international action to hasten the end of apartheid.”

Another letter from Hurd to Thatcher on 18 April 1990 reflected on the position of the then Conservative government. “Our own position is very strong with the government and white opinion”, he said, but adding that the “blacks” were “suspicious”.

He suggested that there was “a large group of radicalised uneducated black teenagers capable of mayhem” whom the ANC may find it difficult to satisfy and control.

The UK government was unpopular in South Africa because Thatcher’s government had been a staunch opponent of economic sanctions against the country. Though Thatcher reportedly did ask the South African President PW Botha in 1984 to release Mandela, she also described the ANC as a “typical terrorist organisation”.

The newly-released documents report that Mandela told a UK government official that he had been “disturbed” by the UK government’s sanctions policy. Though he was grateful for the UK’s educational assistance in South Africa, he pointed out that South Africans were refusing to accept UK-financed scholarships because of the UK government’s attitude over sanctions.

Thatcher’s former diplomats are divided on the impact of her policies on Mandela and South Africa. One of her ambassadors to South Africa has claimed that “no other world leader did more than her to secure his release”.

However, former Foreign Office mandarin Sir Patrick Wright claimed that she wanted South Africa to be a “white mini-state partitioned from their neighbouring black states” and that all her and her husband Denis’s instincts were “in favour of the South African whites.”

Of Thatcher’s successors as Conservative Party prime ministers, both John Major and David Cameron have said that opposing economic sanctions was a mistake. In August 2018 Theresa May declined to answer questions on what she personally did to end apartheid and whether she thought Mandela was a terrorist.

The Conservative Party did not respond to requests to comment.

Photographs of the letters from the National Archives

Photo of Letter With Thatcher’s Comments (Text)

Close Up of Thatcher’s Comments on Letter (Text)

Thatcher Letter Rejecting ANC Funding (Text)

Douglas Hurd’s 18 April 1990 Letter to Charles Powell (Text)

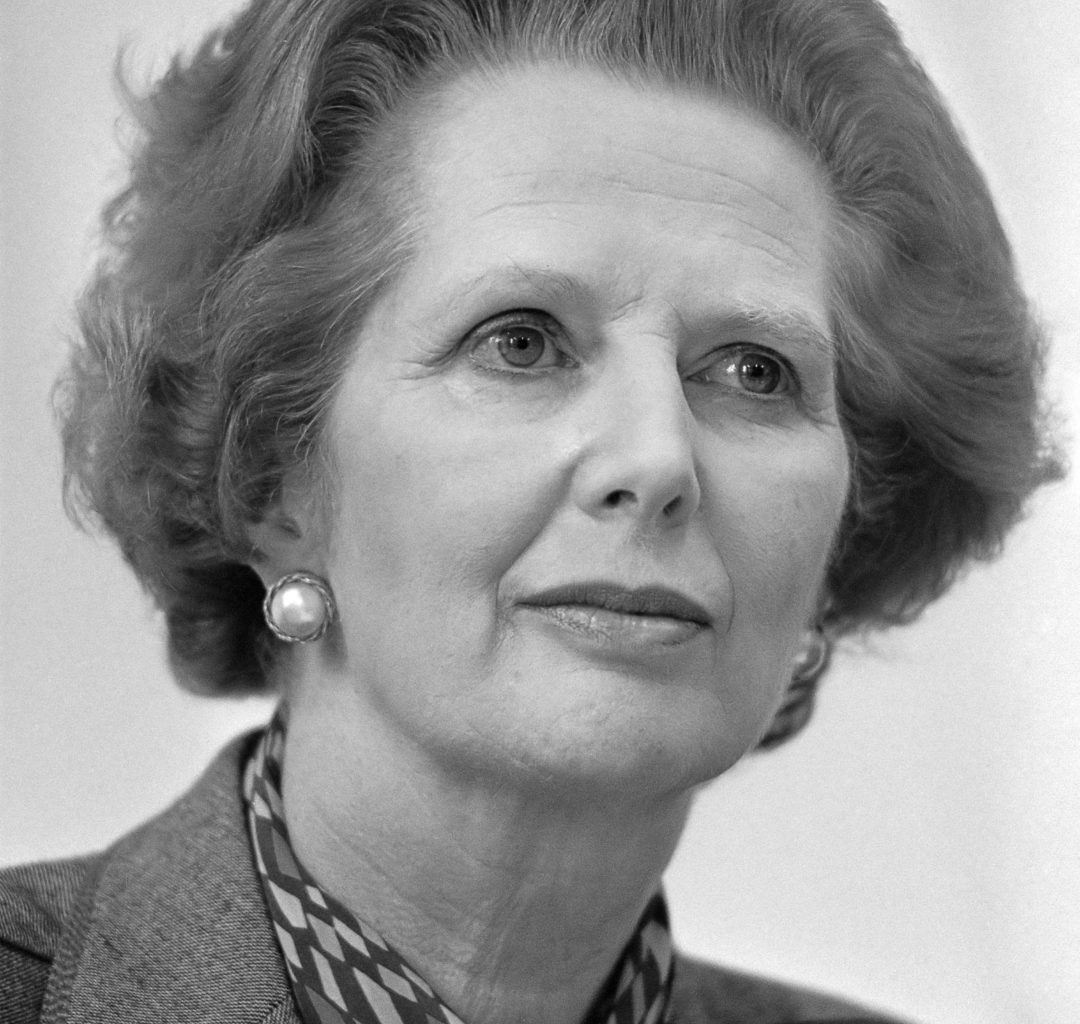

Cover photo: Rob Bogaerts / Anefo (Nationaal Archief) | Margaret Thatcher | CC | Wikimedia. Photo: South Africa The Good News| Nelson Mandela | CC | Wikimedia.