Words by David Donaldson, artwork by Chris Manson.

I am a Scottish Traveller who’s studying at the University of Aberdeen. I’m immensely proud of my people and the rich culture I’ve inherited, but our community faces discrimination and some say the government and media are at war with our lifestyle.

The records show that Scottish Travellers, or Tinkers as we were once known, have been in Scotland since at least the 10th century.

We’ve developed our own language – Cant – our own beliefs and a unique history. Official statistics today place Scotland’s Traveller community at around 4,200 people but some say the true number is between 15,000 and 20,000.

As technology advances and Scotland modernises, we are struggling to retain our traditional lifestyle while often forced to hide our ethnicity for fear of prejudice.

Many within our community say they face barriers due to discrimination and that one of Scotland’s oldest cultures is under threat.

They feel that the government wants to erase their culture, pointing to statements from elected politicians as proof.

A recent comment by Tory MP Gary Streeter gave this argument weight.

Talking about Travellers on an unauthorised encampment, Streeter said: “The key to tackling this perennial problem is to remove Travellers like these from the vulnerable ethnic minority status…they are as vulnerable as Genghis Khan, most of them are as ethnic as I am and all have permanent homes elsewhere in the UK.”

Similar language came from Tory MP Douglas Ross. Answering the question, “If you were prime minister for the day, without any repercussions, what would you do?”, he responded, “I would like to see tougher enforcement against Gypsy/Travellers.”

Both examples sparked outcry from the Traveller community, and rights activists claimed that this rhetoric can encourage discrimination.

To better understand the issues and offer some balance, I was commissioned by The Ferret to interview some people from my community.

These are the voices of young people, proud of who they are, and of being part of an ancient people: these are Scottish Travellers.

George, 23 – Oban

The weather is overcast, seagulls everywhere. Tourists bustle by the young man as he walks along the harbour. George is just one week home after being on the road in the north-east of Scotland when he agrees to meet with me.

George lives in a house with his parents and younger sister but it is clear once he starts talking there is a restlessness to him; he doesn’t like the brick and mortar lifestyle.

I ask if he would stay in a trailer, given the choice?

“I’d bide in a site, I’ve been trying to get a pitch…try get my parents back in that way,” George replies. “Cause they just canny stand the house, even at the weekend my father would rather go away out to the site and stay there the whole weekend. Four walls…it is what it is.”

George’s parents had taken the decision to move his family into a house, leaving the familiarity of the Traveller site behind. In part, this was to allow his younger sisters, who have learning difficulties, to have a better chance at accessing school.

George himself attended primary school, but stayed just one year of secondary – he was initially home-schooled after finishing primary.

“High school was good…I was going a year into school, I got put back a year. But when I was 16 they asked me; ‘look you’re getting in so much trouble is there any sense in you being here?’ I said ‘no, no really’. That was it. I went to college…it lasted three weeks then I got kicked out of that as well.”

George is no exception when it comes to young Travellers receiving little education. Recent government statistics revealed that 28.1 per cent of Gypsy/Traveller students leave school with no qualifications at SCQF level 3 or higher, compared with just 1.9 per cent of non-Traveller leavers.

In George’s case, name-calling led to fighting, cutting his education short.

“It was ‘Gypsy this’ and ‘Tinker that’,” he explains.

Like most Traveller men of his age, George spends his time knocking on doors seeking gardening work and collecting scrap to earn a living. Indeed, like most of his peers, he places great importance in boys learning a trade early on in life. And that trade must be mobile as portable skills allow him to take to the road whenever he gets the chance.

But George says this life is becoming more difficult: evictions are frequent and there’s a growing issue with the number of legal camps available for Travellers in Scotland.

“Up the west coast you don’t get a chance, you only get a couple of days…you get shifted everywhere.”

The shortage of legal stopping places for Travellers is leading to unauthorised encampments across the country. Often these camps are set up in parks, greenbelt land and industrial estates, causing tensions with local, settled communities.

Usually, the local authority’s first reaction is to find a way to evict but Travellers look towards ‘negotiated stopping’ schemes as a better option. These place importance on dialogue between Travellers and councils, with a view to agreeing terms for a camp to remain in one place for a set period.

For George though it’s not just the trouble of finding a place to stay; he faces regular and direct discrimination.

“Depends where you are, if you’re in Arrochar they have signs up in the shops saying ‘No Travellers allowed’…or like when I went out to a pub a few weeks ago when I was down the road, the barman said ‘I’m no serving you because of the colour of your hair, I ken you’re a Traveller’ – he had red hair. I said, ‘that’s complete discrimination’, he said, ‘I don’t give a damn…it’s my pub, my rules – get out!’ Aye it happens.”

George also claims that discrimination has become institutionalised.

“What do you think are the main issues for Travellers in Scotland today?” I ask.

“Young boys getting bothered just for driving about,” George replies.

His claim is backed by many within his community and official statistics show that although Gypsy/Travellers make up just 0.1 per cent of Scotland’s population, they accounted for 0.3 per cent of all stop and searches by the police between 2016 and 2017

Furthermore, a report conducted in 2016 on Stop and Search statistics, found that police were four to five times more likely to search those from ‘other ethnic groups’, with rates particularly high amongst people from the Gypsy/Traveller community.

But despite the continued hardship of being on the road as a Traveller, George has unwavering dedication to his nomadic roots.

“As soon as I get married myself there’s no way I’m going to be in a house. I’ll be here and there all the time. No way be in a house.”

Eliza, 16 – Brechin

Eliza has lived in a house her entire life but she spends every summer on the road. She is hugely proud of her Traveller heritage. Eliza’s family have chosen to live in a house, partly due to the constant evictions that families face when living on the road.

Eliza has completed a full education, attending both primary and secondary education. Her experience of school was positive but her Traveller ethnicity was not something she could freely express.

I ask if she ever faced discrimination or racism for being a Traveller?

“No, because country-people didn’t know.”

“Did you deliberately make sure they didn’t know so that you wouldn’t face discrimination?”

“Yeah.”

Eliza is not alone in hiding her identity from the settled community for fear of discrimination. For her, like many other young Travellers, this is perceived as necessary to access an education, fit in and avoid bullying.

I asked how it felt having to hide her ethnicity at school and around people from the settled community.

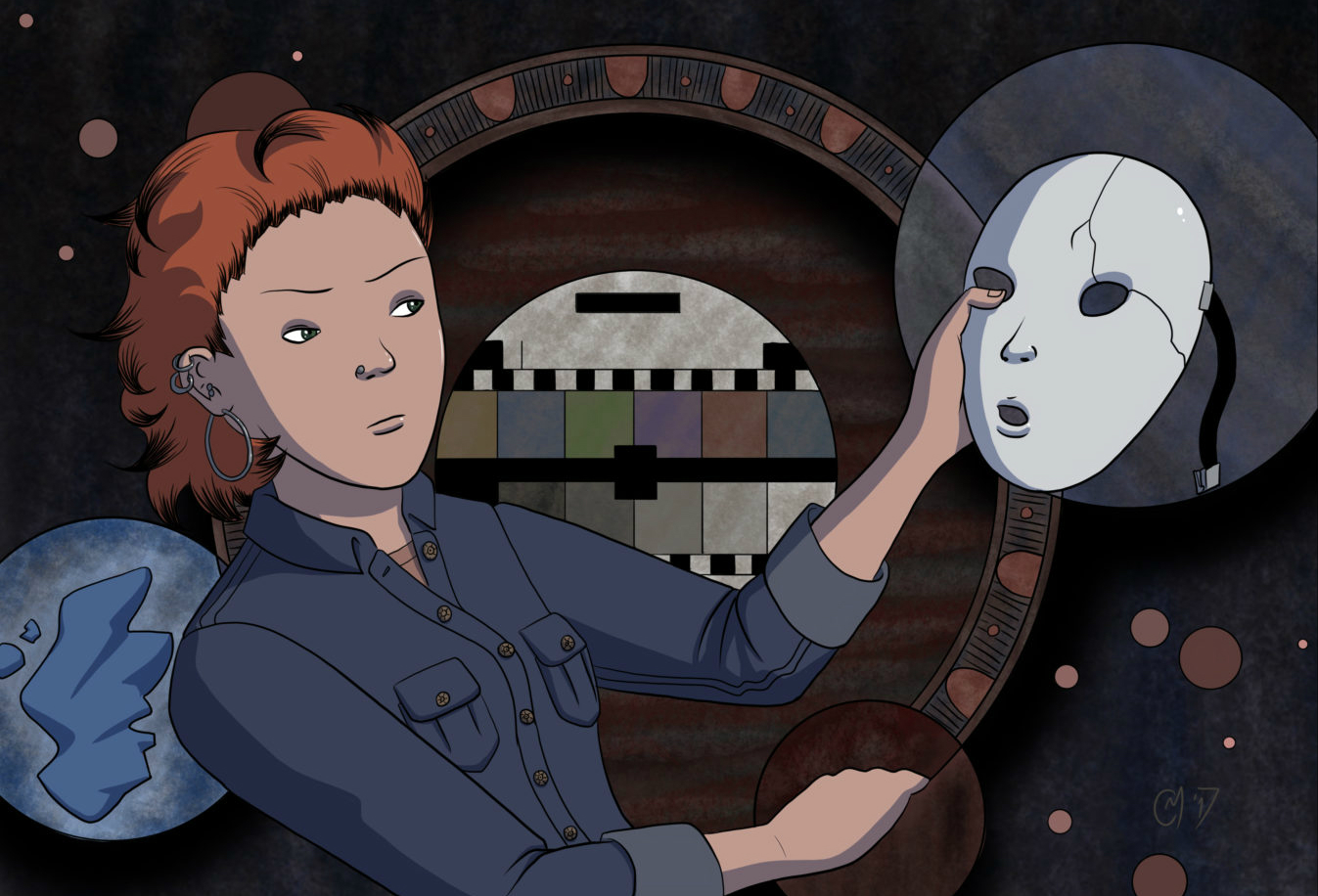

“It’s like wearing a mask,” she says.

Eliza says that as a Traveller she misses out on many opportunities. These life chances include a career.

“I felt that if I was in a career I would always have to wear that mask. Like at work and everything,” Eliza says.

Most Travellers will never enjoy a professional career and with recent studies showing that 34 per cent of the settled community would not agree with a Traveller becoming a primary teacher, many believe that negative stereotypes are the cause.

Eliza believes that Travellers are unfairly characterised by the media.

“Shows like My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding are a cliché of what a Traveller’s like, that’s not what a Traveller is like,” Eliza says.

Does she think that the media, including newspapers, help to promote stereotypes?

“I feel like the newspapers and articles, like the bad ones, brand us as something we’re not.”

Eliza is frustrated with newspaper headlines making claims such as ‘New laws will stop travellers from invading’. She says her culture is home-grown, its history and importance to Scotland often overlooked by the settled community.

“Our culture has been around for centuries, and I feel like country-people just throw that aside as if it’s nothing. Like they focus on history and everything but they don’t mention the history of Travellers.”

Eliza is proud of her people and believes that her community will continue to fight for its rights.

“We stand up for who we are…and since we don’t get the same rights as other people do, we keep fighting for them…I aspire to help others take down their mask and be who they actually are, instead of hiding it because of what other’s opinions are.”

Sophie, 21 – Glasgow

Sophie has lived in a house for most of her life, but still has fond memories of being on the road during her childhood.

“Growing up I was always shifting, going to different camps and sites…wherever I went there was always young Travellers around my age…I always made new friends.”

Despite not having lived on the road for years, she still holds true to her Traveller identity and believes this identity runs deeper than just living in a caravan.

“What would you say makes a Traveller a Traveller?”

“I’d say definitely blood, that’s something I’ve always thought, if it’s in your blood it’s in your blood. I think that’s what makes a Traveller a Traveller. You can always learn the speech or start living that way, but does that make a person a Traveller? You could take someone from the settled community, learn them the language, put them in a trailer – I doubt they’d feel like a Traveller.”

Sophie’s family chose to move into a house primarily due to her mother’s ill-health.

“She can’t be in a trailer because she needs to be close to doctors and living in a trailer would be hard for her, obviously getting in and out of it, and going into chalets in the winters it’s really cold.

“So, we can’t do that type of things anymore but we’d still love to.”

Recent government statistics show that Travellers are five times more likely to suffer poor general health than the settled community. Travellers believe this is due to problems accessing healthcare while on the road.

For many Travellers, healthcare is the foremost motivation to move onto permanent sites but Sophie says her community often face barriers in doing so.

“There’s hardly any sites in Scotland, and most of the sites are run down and they’re not maintained properly,” she says.

Shelter Scotland says there are only 500 local authority pitches available for Travellers, with some only accessible for certain months of the year. Due to the shortage of sites, waiting lists for pitches can be long and many families subsequently struggle to get accommodation.

Attaining a pitch on a permanent site doesn’t necessarily improve access to some services, Sophie claims.

“I know that from some sites the councils wouldn’t accept that as a settled address, so it can be difficult accessing healthcare. It should be easier for folk to see somebody instead of going straight to hospital.”

Sophie claims, speaking from personal experience, that a settled address is often required to register at a doctors surgery; leaving Travellers struggling to access healthcare living on a site.

Healthcare is not the only service which Sophie claims is difficult for Travellers to obtain. She’s learned that Traveller ethnicity can stand in the way of children gaining a safe education.

Primary school went well, she says, but when the transition to secondary came, her peers changed rapidly. They became more aggressive and eventually Sophie found herself bullied for being a Traveller.

“It started with like just name calling, like you know ‘Gypo’, ‘Tinker’, that sort of thing, and then it started to get more aggressive. Like getting tripped up down stairs. Getting pushed in hallways.

“Then it got really bad, when a group of boys about 10 or 12 of them, they came up behind me when I was in the dinner hall just going to my next class and they ended up shoving me across a dinner table…then they started targeting me online – calling me ‘diseased’, ‘pikey’ an all that, so I just kinda gave up on the whole thing…”

Sophie says she didn’t just receive bad treatment from students but also education professionals. She claims that after leaving schooling early one year, in order to go on the road, she was placed in isolation for four months on return – in a room containing only a chessboard.

“I think that’s why other kids thought I was different as well, because I was getting treated different, not just by them, but also by the work staff.”

Many Travellers claim that teachers don’t understand their culture, which results in children being misunderstood and treated unfairly. Sophie says that teachers need to be taught more about Scottish Traveller culture.

“I’d say it’s getting better bit by bit, but most staff still don’t realise. They need more training in Traveller culture. Awareness raising workshops for the teachers maybe, not just the kids because I think they need to know a lot more to be more culturally sensitive.”

Sophie claims that her culture should not be allowed to die out, and that younger generations need more insight into Traveller lifestyle.

“I think I wouldn’t be me if I wasn’t a Traveller, I think it’s what makes you, you.”

Jess Smith – Storyteller

“Could you tell me a little bit about how Traveller life was when you were younger?” I ask Jess Smith.

She puts a cup down and casts her mind back. Jess remembers the old camps near every settlement, children huddled in bow tents (canvas tents) and waggons, and the ancient storytellers sat around fires, with their tales of burkers (body-snatchers) and fairies.

“When I was a wee lassie there were no restrictions whatsoever, no councils closing fields off, you could run free, you could play in fields, you could walk along the riverbank, the natural path that people had tramped on for hundreds of years…there was no restrictions – no signs. Kids were allowed to be kids.”

Smith – a published author and storyteller – paints a contrasting picture of the contemporary Scottish Traveller community. She says that every year now sees another ancestral camp unauthorised while council evictions mean more Travellers are left in a constant state of homelessness.

Without a place to stay legally for any length of time – and with the threat of discrimination due to their ethnicity – many families say they feel forced ‘off the road’ and into housing. It means that young people are losing the chance to hear of bogles and burkers around glowing campfires, as Smith did in her youth.

“Young travellers say pressure is building upon them and their culture, leading to more and more people moving into houses. Some feel they must also hide their identities,” Smith says.

“Jess, you’d say that young Travellers are at a critical time then for conserving their culture?”

“It’s a crucial time for them…we need to stay strong to our roots. It’s a beautiful tree, it has lovely fruit on it, it can be tasted by everybody and anybody, but the minute we start to attack the roots and we don’t water the tree, that’s us attacking our roots and we should never do that.”

Some names have been changed to protect the identity of interviewees.

David Donaldson is currently studying Social Anthropology and International Relations at the University of Aberdeen.

Artwork by Chris Manson.

The above report was funded by The Ferret’s Media Diversity Fund which aims to support journalists and writers from marginalised communities in Scotland.