It’s December in Edinburgh – the penultimate day of the first hearing of the Sheku Bayoh inquiry – and Kadi Johnston and Kosna Bayoh, Sheku’s older sisters, are exhausted.

Nearby, Princes Street’s Christmas markets are bustling. But outside the anonymous looking Capital House – where the inquiry into Sheku Bayoh’s death in police custody in 2015 is being held – there is only a solitary camera crew. Two police officers stand on duty at the door.

On the fifth floor, overlooking the Scottish capital, sits a family who are still suffering. For years they’ve fought for answers, and — since the Crown decided it would not prosecute either officers or Police Scotland — they have been campaigning for this inquiry.

But it’s been a tough process, they admit. During this first hearing, launched last May and held in two parts, family members have sat through 31 days of often emotionally gruelling evidence.

So far the public inquiry, chaired by Lord Bracadale, has looked at what happened to Sheku in the hours and minutes leading up to his death on 3 May 2015.

He stopped breathing after being restrained by up to six officers and was pronounced dead in hospital. This was the first time officers involved in his restraint had given public testimony.

With the second hearing now commencing on Tuesday, 31 January, The Ferret is today launching a new podcast breaking down the evidence that has so far emerged over three episodes.

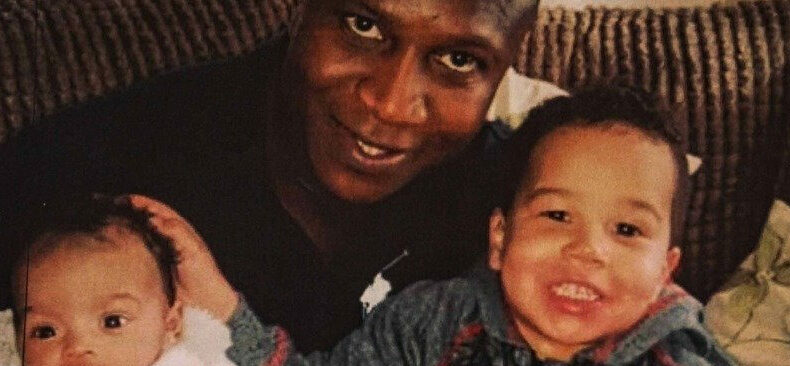

To Kadi and Kosna, the man at the heart of this evidence will always be their “baby brother” – fun loving, friendly and easy to be around. His sons – now 11 and 7 – were his world, Kadi says.

On the December day we meet, the family had walked out of the hearing in protest, after learning that supplementary evidence from PC Alan Paton, due to be broadcast that afternoon, was put on hold due to a motion from his lawyer Brian McConnachie KC.

The former police officer, one of the first on the scene, provided recorded evidence due to a diagnosis of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He retired early from the police due to ill health.

PC Paton had been asked in the inquiry about allegations of racism, made within months of Sheku’s death by estranged members of his family, who claimed he said he “hated all blacks”. He insisted these allegations were malicious smears, driven by a family feud that has nothing to do with the case.

But Sheku’s family want to see this evidence explored. Further delays are difficult for them.

In the inquiry’s family room there have been tears and frustration. “We have waited for seven years for this,” said Kadi at the time. “Why should we wait longer?”

Sheku died here in Scotland. It makes a difference when we know that people are really supporting us.

Kadi Johnston

In recent years the family have spoken out about the outcry in the US over the death of George Floyd – the black man killed in Minneapolis by an officer who knelt on his neck for nine minutes. Floyd’s death in May 2020 sparked widespread protests in the US and ignited global interest in the Black Lives Matter movement.

In Scotland, despite lockdown restrictions still in force, people attended vigils and protests that summer in their thousands.

The protests also re-ignited interest in Sheku’s death. But though small vigils have continued on key dates during the inquiry’s first hearing, to Kadi – sitting in an often sparsely populated public gallery and facing racist abuse online – the interest in Black lives does not seem to have sustained.

Those who have sat with her and shown support have given the family “courage” she says. But she had hoped for a greater groundswell of interest.

“When George Floyd died so many people came out, rallying for him, protesting for him,” she says. “They lit candles. They were crying. And my heart goes out to George Floyd. But Sheku died here in Scotland and I haven’t seen that for him. It makes a difference when we know that people are really supporting us.”

Although the final hearing of the inquiry will be dedicated to the issue of race, the question of what could have been different if Sheku was white is woven into the fabric of each hearing.

Then cabinet secretary for justice, Humza Yousaf, announced the inquiry in November 2021. He said that for the process to be “rigorous and credible”, it must look at whether Sheku’s race played a part in how the incident was approached by the police.

In her preliminary statement that month, senior counsel for the inquiry Angela Grahame KC said the inquiry would be asking questions “at every stage” about what difference it made that Sheku was a Black man.

Campaigners point out that racism in the police is not a far away issue belonging to the US, and that it has a long history here in the UK.

We have found that racial stereotyping – of black men as inherently dangerous or having superhuman strength – as well as perceptions of dangerousness and criminality, results in a police responding with immediate use of force.

Deborah Coles, Inquest

It is 30 years since teenager Stephen Lawrence was killed in a racially motivated attack by a white gang in southeast London and it took 19 years for two members of the gang to be charged with his murder.

A public inquiry, chaired by Sir William Macpherson, concluded that the failings of the Metropolitan Police in the investigation of Stephen Lawrence’s murder amounted to institutional racism.

In 2017 Elish Angiolini reviewed all deaths after contact with the police. She found a disproportionate number of Black people were dying in custody, especially after the use of force.

Asked about their knowledge of Black deaths in custody, the Kirkcaldy police officers talked about Black Lives Matters and cases in the US. But most said little about deaths in UK police custody.

They were asked too, about their awareness of common stereotypes of Black men, an issue UK campaigning organisations such as Inquest, claim can lead to excessive use of force.

Director Deborah Coles says: “We have found that racial stereotyping – of black men as inherently dangerous or having superhuman strength – as well as perceptions of dangerousness and criminality, results in a police responding with immediate use of force.

“My frustration and sadness is that time and again, we see these very pernicious and dangerous stereotypes, resulting in that use of force, and dangerous use of restraint.”

Officers were asked about their own perceptions. Sheku was 5ft10 tall and weighed 12st10, about half the weight of PC Craig Walker who was 25st and six foot four. Alan Paton was the same height and weighed 17st.

But the inquiry heard that PC Kayleigh Good described Sheku in her statement to the Police Investigations Review Commissioner (PIRC) as “massive” and “the biggest male that I have seen”. Questioned, she clarified that she meant he was the “biggest male she had ever seen at a police incident”.

Inspector Stephen Kay, who oversaw Kirkcaldy police station, was also questioned about his assertion in a phone call that Sheku was “the size of a house”. In the same phone call he wrongly claimed that Sheku had run at police with a knife. He claimed he must have been briefed to this effect.

Use of force

The use of police force was a key line of questioning. The inquiry team established that within 75 seconds of arriving at the scene officers had sprayed Sheku with CS or Pava spray six times which officers said had no impact, been hit to the head and body several times and shoulder charged to the ground.

Asked about this, police expert witness Joanne Caffrey said this “seemed to be a lot in a small period of time”. Both she and Martin Graves, another police expert called in this hearing, agreed that police could have had a different result if they had not rushed in.

“I think, if the decision had been made to engage Mr Bayoh in a more communicative way – asking how he was, what’s going on – they might have gleaned more information,” Martin Graves said in evidence.

“Unfortunately that wasn’t the case. The officers decided on this verbal dominance approach. It’s difficult to step back from that.”

But officers maintain they had no choice. They insist all force used was proportionate, necessary and followed police procedure. Sheku, who had taken drugs, did not respond to their commands to “get down on the ground” or “stay back”, they said in evidence.

He then punched then officer Nicole Short – who was only five foot one – to the head, causing her to fall to the ground. PC Tomlinson and PC Walker have testified under oath that he then stamped on her back. “I thought he’d killed her,” PC Tomilson said in evidence.

But Short, who also has PTSD, did not remember the stamp, being told only afterwards. Doctors who examined Short after the incident said they had not recorded injuries that supported the claim. Experts who examined marks on the back of PC Short’s vest, which she and others claim could be a footprint, claim their own evidence is inconclusive.

One claimed that while he could not rule out the possibility the mark was a footprint, it didn’t correspond with “the pattern elements” of Sheku’s shoe. The other found that both the soil samples on the boot and the PC’s vest came from “the same origin source” but said she could not conclude that meant his boot made the mark.

I would argue that the actual issue is not that they are unconscious of the reality but that, because it is psychologically uncomfortable to acknowledge the ways in which we all collude with racism

Gillian Neish, equalities trainer

Asked if the situation would have been any different if Sheku had been white, all are adamant it would not. All told the inquiry they were unaware of any racist comments or jokes made by police and would challenge any that arose.

But the inquiry was also shown footage from Kirkcady police station’s custody suite where an Edinburgh-based officer, accompanying a prisoner of middle eastern origin, joked with PC Brian Geddes about “ISIS in the station”.

Initially he said he didn’t remember the incident. Later he clarified in a written statement to police that he had raised it with his superiors.

Whether the inquiry finds that racism played a role in Sheku’s death or not, Police Scotland has acknowledged its need to do more to tackle the issue.

In an opening statement read on behalf of Iain Livingstone, chief constable of Police Scotland by his lawyer Maria Maguire QC said it was “not enough to be non-racist”. “Police Scotland needs to be anti-racist,” he said.

Livingstone told The Ferret this week he was fully supportive of the inquiry, and had met with both Sheku Bayoh’s family to express his condolences as well as meeting officers involved. “We must respect the authority of Lord Bracadale and allow the Inquiry to establish the facts and carry out its important work,” he added.

According to Gillian Neish, a specialist trainer in race and equality, becoming an anti-racist organisation will be far from easy work. It means “acknowledging that racism exists, and actively challenging the systems and structures, policies and procedures, attitudes and behaviours that maintain and perpetuate it whilst also promoting inclusion,” she says.

She claims “unconscious bias” is an excuse to not getting to the root of the issue.

“I would argue that the actual issue is not that they are unconscious of the reality but that, because it is psychologically uncomfortable to acknowledge the ways in which we all collude with racism, they adopt a position of cognitive dissonance to avoid feelings such as guilt, shame and fear about knowing the system is unfair,” she says.

Anti-racist policing, she points out, is not a favour to people from black and racially minority communities. “It’s about fairness and justice for us all,” she adds.

Though she agrees training can be a support as organisations work out the best ways to implement anti-racist policies, she argues is often not a training issue. She believes leadership is needed to support conversations, with accountability measures built in.

Meanwhile, Sheku’s family are preparing for another difficult hearing and this time they will be giving evidence as well as sitting in the public gallery.

They cannot bring him back. But what gives them strength is the hope that this inquiry can help bring about positive change for everyone.

His sister Kadi says: “Sheku died here in Scotland. And as a family we are fighting for changes to happen in Scotland. No family should suffer the way that we are suffering. So I urge people to support us during the next hearing.”

The Ferret contacted the legal representatives of the officers. Most either declined to comment or did not respond. But Professor Peter Watson, the lawyer representing both Nicole Short and PC Craig Walker claimed “much of the ‘comment’ in Ferret’s email was “inaccurate if not wrong”. “There is a new chapter of evidence which is about to be heard which will go some way to correcting the narrative outlined in your email,” he added. The Scottish Police Federation was also contacted but did not respond.

Listen to Sheku Bayoh: The Inquiry, a three-part podcast from The Ferret covering the evidence so far.

To make this podcast we’re spent hours listening to all of the evidence so we can summarise it for you, our listeners. And we need your support to do more.

Join us at theferret.scot/subscribe and get three months free with the code PODCASTOFFER

This Ferret story was also published with the Sunday National. Our partnerships with other media help us reach new audiences and become more sustainable.

What you have to remember is this took place in Fife, where the police don’t normally get these types of calls. Had it been in Glasgow or Edinburgh the officers might have reacted differently.

Fear, panic all played a part but race I would suggest was not uppermost in their mind.

The defence witnesses are to say the least slanted and all part of the,” hindsight “ group.

Anwar has spent a lifetime looking for something that’s not there, in order to promote himself.

The result a toxic mess, where only the family lose caught up in the belief peddled by others.

Please respect the dead and the living and fix Sheku’s name in the second last paragraph.