A Scottish artist has produced a video and finished a series of portraits to mark the first anniversary of the yet unexplained disappearance of 43 students in Mexico.

On the 26/27th of September 2014, a group of Mexican students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Teacher Training School in Ayotzinapa, were attacked by police in the city of Iguala, Guerrero state.

The students attended a college which is famously rebellious and made the journey to Iguala – about a 90 minute drive away – to commandeer buses to use in a later protest.

During an armed attack by police, six people – including three students – were murdered and 43 other young men from the college disappeared, and one year later relatives of the missing men are still seeking the truth.

The tragic event highlighted forced disappearances in Mexico – more than 25,000 people have vanished since 2007 – and sparked a year of protest and the onset of an international movement to seek justice for the missing students, and tens of thousands other Mexicans who are referred to as “the disappeared”.

Jan Nimmo – a Glasgow based artist and filmmaker – travelled extensively in the state of Guerrero some years ago to document the work of local artisans and musicians.

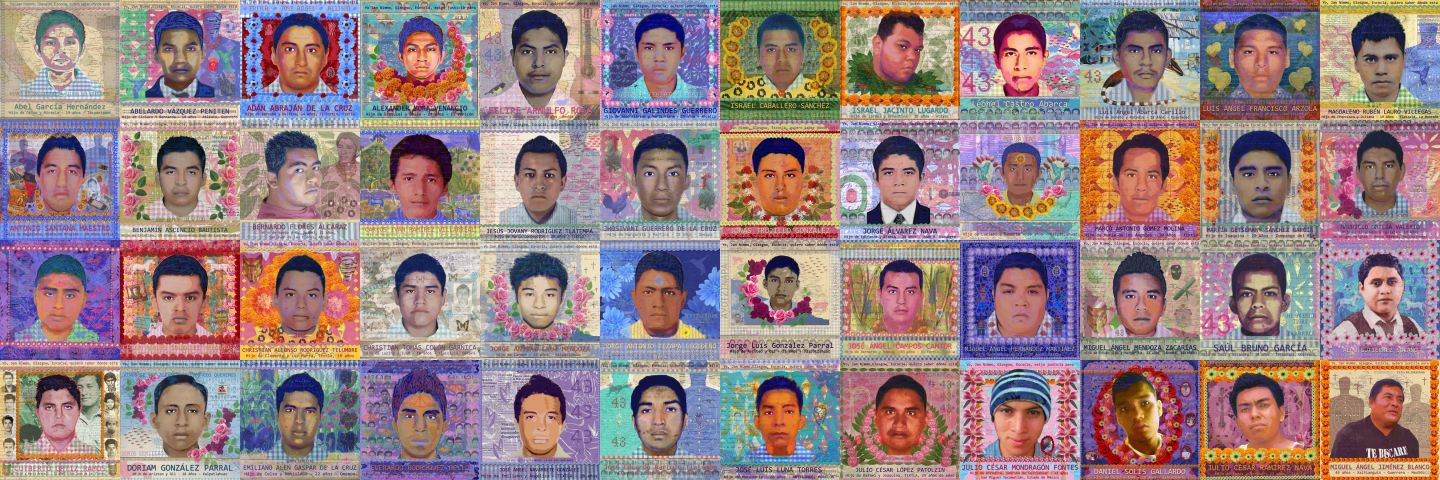

In October 2014, she decided to make portraits of each of the 43 missing students in order to raise awareness of the issue and the high number of disappeared people in Mexico.

Nimmo has now completed all 43 pictures and produced a video, in a show of solidarity with the families of missing people.

She said: “A year ago when I started making the portraits of the 43 disappeared students I had absolutely no idea where it all was going. All I knew was that I wanted to use my day job skills as an artist to highlight this atrocity and to put a face to the 43 missing boys.

“Over the last year I have become more and more absorbed, to the point where realizing this body of work became a compulsion, especially as, over that time, I have gradually built up a solid core of contacts who are social activists in Mexico, and I am even in contact some family members.

“I achieved this mainly through using Twitter, which is a popular tool for Mexicans who are campaigning about the massive number of disappearances that take place literally every day.”

During the past year, Nimmo’s portraits have been used by various organisations in Mexico, Europe and the USA, who are campaigning for the truth, and she has collaborated with social justice activist Eréndira Sandoval Carrillo in Mexico City, who is in regular contact with the parents of the missing students.

Carillo has collected and verified the personal details that form the distinguishing features of Nimmo’s artworks.

She also arranged for banners with Nimmo’s portraits to be printed for the parents, who will each receive a print today (26th of September 2015) to mark the first anniversary of the disappearances.

Nimmo said: “The parents, who have remained dignified and tenacious, have endured so much over the last year, and watching from here it feels to me that disappearing a person is not only a violent act perpetrated against an individual but is also a particularly cruel form of torture for those left behind.

“There is no closure; only answered questions, dark imaginations and a relentless struggle against a state that disappears its own people. Ayotzinapa is not just about 43 students; these boys now represent the many other thousands of disappeared people in Mexico.”

Nimmo’s art has featured in the Sunday Mail and La Jornada, Mexico’s most respected newspaper, and her portraits will be displayed at the Centro Cultural Kirchner, Buenos Aires, Argentina, on the 30th September 2015.

The pictures will also be exhibited in New York, USA, at the Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz Memorial Centre as part of the Tribute to the Disappeared initiative.

In October, Nimmo’s video will be shown at the Document International Human Rights Film festival, Glasgow, and it will be screened at events in Paris and Melbourne.

Last year Mexican authorities said the students were abducted by municipal police and turned over to members of a local drug gang, who killed them and incinerated their bodies.

Under pressure to respond last November, the then attorney general, Jesús Murillo Karam, provided a version of events that has since been contested.

Karam said municipal police from Iguala and the neighbouring municipality of Cocula, working in coordination with a local drug gang known as Guerreros Unidos, had attacked the students as they returned to Ayotzinapa in the buses, probably because they suspected they were linked to a rival drug gang known as Los Rojos.

Karam said police handed the students over to members of Guerreros Unidos, who took them to a rubbish dump outside Cocula where they were killed and burned on a pyre, before their remains were collected in plastic bags and dumped in a river.

However, families of the missing men refuse to believe this official version and are demanding the truth from the authorities.

Ahead of the first anniversary, an investigation by an international panel of experts appointed by the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) released on September 6th, contradicted the above version by Karam.

In a damning 560-page report, IACHR said the vicious nature of the attacks, indicated a more sinister plot, refuting the government’s account of the students’ fate.

“This report provides an utterly damning indictment of Mexico’s handling of the worst human rights atrocity in recent memory,” said José Miguel Vivanco, the Americas director at Human Rights Watch.

He added: “Even with the world watching and with substantial resources at hand, the authorities proved unable or unwilling to conduct a serious investigation.”