Plans to gasify coal under the sea around Scotland could cause pollution, earthquakes, underground explosions and “uncontrollable” fires, according to confidential draft reports from the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (Sepa).

The Scottish Government’s green watchdog admits that it doesn’t know what level of protection its safety regulation can provide against the hazards of underground coal gasification (UCG). The risks were “sometimes unknowable”, it says in one report.

The revelations have prompted anger from politicians, community groups and environmental campaigners. They are demanding that the government’s temporary moratorium on UCG be turned into a permanent ban.

“There are major concerns about the environmental impact and the health and safety implications of UCG ,” said the SNP MP for Edinburgh East, Tommy Sheppard, a leading critic of the technology.

“This is a vindication of the Scottish Government’s decision, backed by the SNP conference, to extend the moratorium to cover UCG. It puts a very serious question mark over whether this technology should ever be part of the energy mix.”

Two companies have licences to investigate UCG in five areas around the Firth of Forth, and a sixth area in the Solway Firth. One is led by the veteran oil entrepreneur, Algy Cluff, and the other is backed by the UK’s largest private landowner, the Duke of Buccleuch.

After pressure from SNP activists and community groups, the Scottish Government announced a moratorium on UCG on 8 October. It appointed Sepa’s former chief executive, Professor Campbell Gemmell, to lead an investigation into the risks posed by the technology.

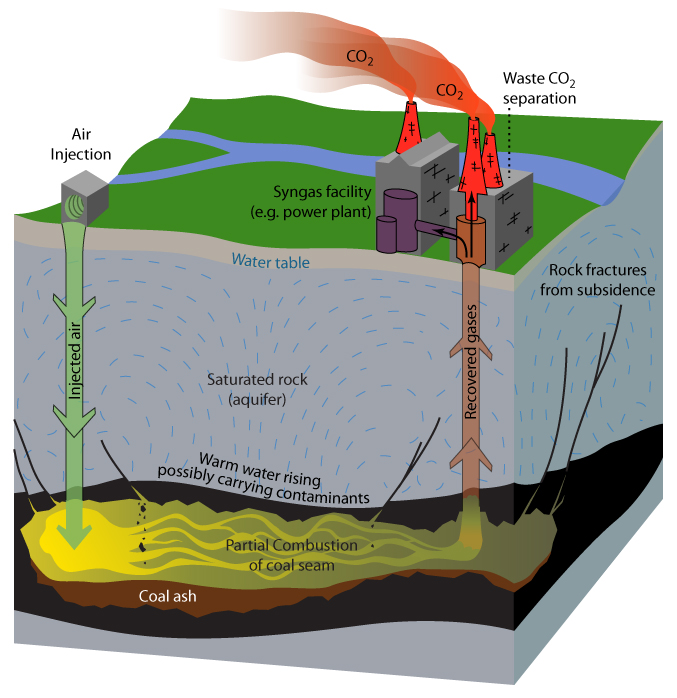

The temporary ban on UCG is in addition to the moratorium placed on the related technique of fracking for shale gas in January this year. UCG involves drilling boreholes up to a kilometre deep, setting fire to coal seams, and extracting the resulting gas to heat homes.

How Underground Coal Gasification Works

In preparation for regulating the technology, Sepa scientists have drafted reports outlining the potential hazards. A first draft from early this year and a second, marked “confidential” and dated July 2015, have been released under freedom of information law.

Drawing on evidence from UCG facilities in Europe, the US and Australia, the reports list eight things that can go wrong. Groundwater can be polluted by toxins such as phenols, cyanides and radioactivity, they say.

Air can be polluted by highly toxic particles, ash, heavy metals and a series of hazardous gases, says the latest draft. Emissions of the greenhouse gases that disrupt the climate are estimated to be lower than from coal but higher than from natural gas though “large uncertainties remain”, it warns.

There is a risk that “induced seismicity” could damage boreholes and surface installations, as well as spread pollution. Underground explosions, which have been recorded abroad, could inflict similar damage, Sepa says.

Igniting the coal underground could lead to “uncontrollable fire”, which would worsen water and air pollution. The danger of underground “cavity collapse” could cause subsidence on the surface.

“The fundamental cause for concern with regards to UCG is that the conditions under which the reaction takes place are naturally variable and difficult to know (sometimes unknowable), placing an inherent limitation on process control,” says Sepa’s first draft. “This, combined with a number of significant environmental and human health hazards, creates risk.”

The more recent draft points out that some of these risks could be reduced if developers drill down to more than 800 metres below the sea, as they plan to do. But it doesn’t say the risks could be eliminated.

There are “significant technological and knowledge gaps”, it warns. Because controls and regulations are still being clarified ”it is not possible at this stage to assess the level of protection they will provide.”

Emails released in response to a freedom of information request also reveal that Sepa was anxious to alter the minute of a meeting with the UK government officials discussing UCG in February 2015. Sepa sought to remove a sentence questioning whether there was “a robust regulatory environment in place”.

The eight hazards of underground coal gasification

| Groundwater pollution | toxic gases and metals could contaminate the ground and possibly find their way into drinking water |

| Surface water pollution | toxic gases and metals could contaminate the sea and other surface waters |

| Air emissions | ash, particles, metals and gases could pollute the atmosphere, risking health and worsening climate change |

| Underground explosion | inflammable gases could be ignited by a spark and explode, damaging boreholes and buildings |

| Cavity collapse | underground cavities could collapse and cause subsidence on the surface |

| Seismicity | earthquakes that would damage boreholes and surface installations, as well as spread pollution |

| Groundwater depletion | other users could be deprived of water, and environmental damage could be caused |

| Uncontrollable fire | underground coal could burn out of control, causing air and water pollution and risking cavity collapse |

Juliana Muir, a mother in Portobello, Edinburgh, who founded the campaign group, Our Forth, said: “This is a truly scary list of potential disasters that no community could be expected to tolerate.”

The dangers of UCG had prompted protests by thousands across the Forth, she added. “The unproven benefits for the few are not worth the risk for many.”

Audrey Egan from Frack Off Fife argued that Sepa’s reports showed that the Firth of Forth was not suitable for UCG. “The area will be subject to health, ecological and environmental threat and that is something we simply must not risk,” she said.

Lang Banks, director of WWF Scotland, pointed out that Sepa had “toned down” the language it used between different drafts. Nevertheless the released reports revealed “a damning list of environmental problems”, he said.

“This is a technology Scotland shouldn’t be touching with a barge pole . It’s also abundantly clear that there remain many serious questions about whether it’s possible to regulate UCG in a robust way.”

Speaking from the world climate summit in Paris, Banks suggested that the aim should be to phase out fossil fuels. “It seems mad that we’d even think of locking ourselves into yet another fossil fuel and a higher carbon future,” he said.

Sepa stressed that the reports had not been completed. “They are not final reports outlining credible risks from the technology in Scotland, rather an initial scoping which includes a range of areas which may be added to, or screened out, as knowledge develops,” said Sepa’s senior policy officer, Emma Taylor.

“The assessment of potential risk requires significant additional work, and during the moratorium Sepa will continue to work with Scottish Government, Professor Campbell Gemmell, and other regulators, to ensure we have the appropriate controls and regulations to protect the environment and human health.”

According to Taylor, Sepa had sought to change the minute of the February meeting with UK officials to more accurately reflect what Sepa had said.

A spokeswoman for Cluff Natural Resources, which has three UCG licences in the Firth of Forth, said it had not seen Sepa’s reports. “We look forward to seeing the final report and hope that it provides a strong basis for the regulation of UCG in the UK,” said a company spokeswoman.

“Given that we are at the early stages of the moratorium process – with an expected independent review of the evidence by Professor Campbell Gemmell – we welcome any research that Sepa can offer.”

Five Quarter, the Newcastle-based company backed by Buccleuch, did not respond to requests to comment last week. It has two UCG licences for the Firth of Forth and one for the Solway Firth.

The Scottish Government stressed that it was taking “a cautious, evidence-based approach” to UCG. The moratorium would “allow necessary time for full and careful consideration of the potential impacts of this new technology,” said a government spokeswoman.

Problems abroad with underground coal gasification

Six attempts to set fire to coal underground and tap the resulting gas have resulted in leaks, pollution, explosions and ill-health at plants around the world, according to Sepa.

At El Tremedal in Spain an ignition system malfunctioned and a temperature gauge failed, causing “accumulation of methane and a subsequent explosion”, a draft Sepa report said. The 550-metre well was damaged and shut down in 1997.

The plant, which gasified 240 tonnes of coal, also contaminated groundwater. “This was a major technical and economic problem,” the report said.

An experimental 30-metre mine called Barbara in Poland suffered similar problems in 2013. “Cracks developed causing gases to leak and create explosive accumulations, igniting due to high temperatures,” Sepa reported. “Heavy metals, ammonia and cyanides found in effluents and groundwater near the site.”

The 150-metre deep Chinchilla mine run by Linc Energy in Queensland, Australia, from 2007 to 2013 caught fire because of a coal tar blockage. Toxic gases also leaked to the surface after well casings cracked under pressure.

According to Sepa, “uncontrolled leaks” of gas made workers ill. The Queensland government has launched a £3 million criminal court action on Chinchilla, alleging “extensive” pollution and “irreversible” harm, denied by the company.

A 150-metre mine at Bloodwood Creek that opened in Queensland in 2008 had a different issue. “An injection well blockage caused pressure to spike well above hydrostatic pressure, resulting in the emission of process water through the flare,” Sepa said.

At Hoe Creek in the US during the late 1970s a 50-metre well resulted in long term contamination. “Cavity collapse caused serious groundwater pollution and subsidence could be seen at the surface,” said the Sepa report.

A series of underground coal gasification trials in the former Soviet Union in the late 1950s and early 1960s contaminated groundwater. The pollution was “found to be widespread and persistent, even up to five years after production had ceased,” reported Sepa.

“Phenols were found within an aquifer which extended over an area of 10 square kilometres. There were significant gas losses due to leakage, and it was common for between five per cent and 25 per cent of the gas formed to be lost from the underground gasifier.”

First draft of Sepa report on UCG hazards

Second draft of Sepa report on UCG hazards

Sepa revises minutes on UCG regulation

Graphic thanks to Bretwood Higman, Ground Truth Trekking, licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Commons.

Cover image thanks to Chris Combe, image has been modified.

Photo thanks to Michal Osmenda via Wikimedia Commons.

A version of this story was also published in the Sunday Herald on 6 December 2015.

Such a shame agenda of supposed ‘meeting’ to discuss community groups concerns re UG, fracking and public health- for Public Health Impact Assessment on UG-left community groups with virtually no time to speak.