The Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland or GERS report has been the subject of much political football.

In the run up to the 2014 referendum and beyond, politicians on both sides of the constitutional argument have used the report to shore up their economic arguments.

Ferret Fact Service takes a look at GERS and the meaning behind its headline figure – the deficit.

What is the deficit?

The E in GERS stands for expenditure and is the total of all public spending for the benefit of people living in Scotland. The R stands for revenue which is mainly tax but also includes money from other sources such as parking fines and surpluses from public bodies like Scottish water.

The deficit is a one-number summary of the fiscal situation, where fiscal just means tax and spend. You can think of the deficit as the shortfall in annual public finances.

The deficit is simple enough to calculate, you just subtract total revenues from total spending.

The main headline from the latest GERS for the financial year 2016-17 is that the deficit is big, being £13.3 billion, or 8.3 per cent of GDP – the total value of everything produced in the Scottish economy including Scotland’s share of North Sea activity.

EU countries are supposed to keep deficits below 3 per cent of GDP, but this limit is often broken and larger EU countries breach it without significant consequence.

Is a big deficit a problem for our governments?

Under current arrangements the deficit is not a problem for the Scottish Government because it is absorbed into the UK’s overall deficit which is currently 2.4 per cent of its GDP.

Following the recession in 2009-10, triggered by the global financial crisis, the UK’s deficit peaked at 10 per cent. This was mainly due to a fall in tax revenues but also from increased public spending on benefits due to unemployment.

Scotland’s deficit was also 10 per cent that year. Without North Sea revenue, Scotland’s deficit would have been 16 per cent and the UK’s 10.5 per cent.

Strong warnings were issued that the UK’s high post-crisis deficit would cause total public debt to rise and that would drive up interest rates making future borrowing more expensive. This proved to be incorrect.

In fact, over the time period GERS covers, UK public sector interest payments dropped from 3 per cent of GDP in 1998-99 to 2 per cent in 2016-17 even though UK public sector net debt increased from 36 per cent to 82 per cent.

The reason these warnings were wrong is their claim was based on a faulty premise – that a country’s finances are like a household’s.

Why are UK public sector finances not like a household’s?

There are two main reasons. The first is that a state with its own currency and central bank can create money and influence how it flows in the economy by setting interest rates. No household can do that.

Governments rarely choose to fund their deficits by creating money, and the EU explicitly forbids it in Article 123 of the Lisbon Treaty.

Instead, governments choose to borrow an amount roughly equal to the deficit by issuing debt carved up into chunks called bonds. In theory, if a government issues too many bonds, the interest rate it has to pay on this debt will go up.

In practice, as reflected in UK numbers above, this does not always happen because financial institutions view such bonds as an extremely safe investment precisely because they are backed by a state which can create its own money.

For the same reason, demand for bonds goes up in uncertain economic times and their interest rates come down. This does not apply if a country builds up debt in a foreign currency, as is the case in Venezuela.

The second reason is more subtle. For most households, income comes from one source, usually a job, and outgoings go elsewhere, such as to companies that run shops. But the UK public sector is quite different. Its income comes from taxing all parts of the economy and its spending is also a very substantial part of that same economy, about 40 per cent of GDP.

This means that although our governments can alter tax rates and public spending, it’s hard for them to control the deficit because tax and spending are linked together via the mass psychology of all households and businesses in the economy.

A simple example illustrates the point. If a household decided to save money inside a year by cutting its spending in half by choosing not have holidays and meals out and suchlike, that would not affect their income.

If a government halved its spending inside a year it would send the economy and society into crisis and income from tax revenues would fall significantly.

Why is Scotland’s deficit so large?

Mainly because public spending is high, being £13,175 per head. For the whole UK, it is significantly less at £11,739 per person. Also, although Scotland’s revenues used to receive a sizeable boost from the North Sea, this has dropped markedly in recent years and now Scotland’s revenue per person stands at £10,722, somewhat lower than the UK’s £11,035.

Reasons given for why Scotland’s spending per head is so high include the costs associated with providing public services to remote areas due to its lower population density and also because Scotland has greater needs due to issues such as poverty and health.

Whether this is true or not, the reason such high spending is possible is because the Barnett formula provides more funding per head to Scotland than is available elsewhere in the UK. No aspect of that formula explicitly addresses need and its above population-share funding for Scotland appears to be an historical accident of arithmetic.

Didn’t GERS show onshore revenue growth last year?

Yes. Scotland’s onshore (non-North Sea) revenues grew by 6 per cent in cash terms or 4 per cent in real terms (inflation adjusted) between 2015-16 and 2016-17. But these gains aren’t explicable from the rather poor 1 per cent growth in Scotland’s onshore economy in that time.

Also, the fact that the UK’s revenues grew at about 4 per cent too suggests that the explanation is not peculiar to Scotland.

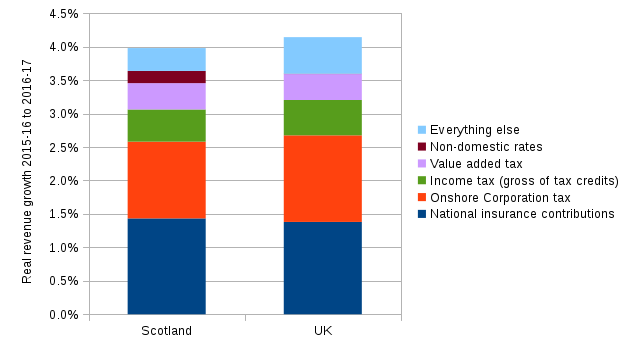

The chart below shows a breakdown of which taxes contributed to the revenue growth in Scotland and the UK.

Both are similar and show the majority of the rise is due to National insurance contributions and corporation tax.

National insurance rose due to the changes made by UK chancellor George Osborne in his 2013 budget which came into effect on 1 April 2016. These can be viewed as a regressive tax rise as they affect lower earners more in percentage terms.

Entirely separate to that, corporation tax, which is calculated as a percentage of profits, has risen because of crack-downs on corporate tax avoidance but also because companies have seen a boost to their profits in 2016-17.

There are likely several reasons behind this surge in profits, but one suggestion is that companies are not passing on such gains to employees in wage rises because they fear the gains are temporary amidst the uncertainty from Brexit.

When would the deficit become a problem?

Deficits are not unusual. Except for a small surplus in 2000-01, Scotland has had a deficit from 1998-99 to 2016-17 and the UK has had a deficit since 2002-03. Out of 26 OECD countries for which data is available for 2016 (calendar year), 15 of them ran deficits, including large economies such France, Japan and the United States which have all run deficits for over a decade.

A deficit can be viewed as a flow from the public to the private sector, and from the numbers given above for Scotland it amounts to about £2500 per person. Whether this is desirable or not depends on your point of view.

If growing public services and redistributing resources are priorities then it could well be a positive. Against this are concerns about the size of the state. In other words, that a single actor – the government – with control over 40 per cent or more of GDP might produce unhealthy distortions in the economy.

People holding to this second viewpoint would argue for a decrease in the deficit and perhaps even aim for a public surplus.

A separate issue is that large deficits can cause problems through borrowing in certain circumstances.

For example, if a country:

- has persistently low GDP growth

- imports more than it exports, especially with a dominant trade partner

- does not control its own currency

In these situations, a large deficit can lead to mounting debt owed to other countries. Of these points, the last one explains why the UK could deal with a post-crisis large deficit by itself, whereas Greece and Ireland, which use the Euro, were forced to comply with strict EU and International Monetary Fund conditions in return for help with their growing debt burden.

Guest post by data scientist Dr Andrew Conway, writer of An Active Citizen’s Guide to Scotland.

Correction: This explainer originally stated that Scotland had run a deficit every year from 1998-99 to 2016-17. It has been edited to acknowledge a small surplus in 2000-01.