Eight privately financed schools in Scotland with potentially dangerous defects that were hidden from parents can be named after an investigation by The Ferret.

Council officials withheld details from parents, despite an independent inquiry into the Edinburgh school wall collapse at Oxgangs Primary School in February 2016, concluding that “only luck” had prevented pupils from being killed by construction errors.

Checks conducted after the Oxgangs incident found that five schools in Angus and three in Dundee had construction defects similar to those found in Edinburgh schools.

Repairs to the Dundee and Angus schools were undertaken in the later months of 2016, but neither the names of the schools, nor specific details of the flaws that were found, have been released by the two councils.

The Ferret used freedom of information legislation to obtain the names of the schools, and as much documentation as possible about the problems that were found in the buildings that needed to be repaired.

Craigowl Primary School and St Andrew’s Roman Catholic Primary School in Dundee were found to have defects, as well as Grove Academy in Broughty Ferry.

A letter dated 11 November 2016 from Fergus Wilson, Dundee City Council’s head of property, to the government’s Scottish Futures Trust summarises the problems.

He said that three wall panels in the Dundee schools were found to be “operating at a factor of safety less than structural design codes require.”

At two of the schools affected, the letter said: “Wall panels were found to be missing some bed joint reinforcement and/or some wall head restraint ties. Both required by design and specified as part of the construction drawings.”

At one school, unspecified in the letter, Wilson reported that: “…wall tie embedment was found to be below minimum design requirement at some locations and several wall panels were missing their specified wall-head restraint ties.”

To tackle flaws in the Dundee schools, the letter said that repairs began in the summer of 2016, and were completed in the October holidays.

A spokesman for Dundee City Council said: “Parents were not notified since at no stage were the schools considered to be at risk or unsafe for occupation and as the deficiencies were rectified with no real impact on the operation of each school.

“The deficiencies were rectified at the contractors’ own cost and as there was no real impact on the operation of each school there was no financial penalty applied.”

Dundee officials, in their letter to the Scottish Futures Trust, also noted that other school buildings in the council area, of a similar age and construction but built outwith the public private partnership (PPP) finance model, were found not to have any defects when they were inspected.

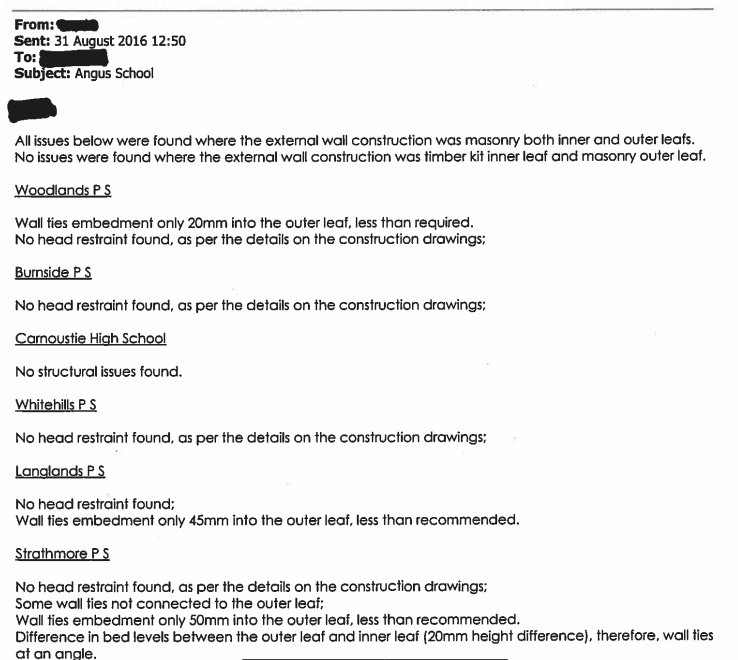

In Angus, five further schools were found to have construction flaws so critical that remedial works were required. They were Burnside Primary and Woodlands Primary in Carnoustie (report pt1, report pt2), and Strathmore Primary, Langlands Primary and Whitehills Primary in Forfar (report pt1, report pt2).

Woodlands, Langlands and Whitehills were found to have walls where the ties were not properly embedded in the brickwork.

Angus PPP School building flaws

As in Dundee, officials said no teaching days were lost because of the repair work undertaken to fix the Angus schools. Private companies involved in the schools also picked up the bill.

An Angus council spokesperson said: “The defects had no disruption to the service use of the buildings and therefore parents and young people were not impacted. Work was carried out during the school October holidays (2016) and weekends, and there was no risk to pupils at any time prior to that.

“There were no financial penalties levied against the PPP Contractor. The Contractor carried out surveys and remedial works at their own cost.”

But according to Professor Alan Dunlop, Honorary Chair in Contemporary Architectural Practice at Liverpool University, who gave evidence at the Edinburgh PPP Schools inquiry, some of the faults found in Angus and Dundee schools were very similar to those identified as the primary contributory factor to the collapse of the wall at Oxgangs Primary.

The Edinburgh inquiry identified the main cause of the Oxgangs wall collapse to have been “insufficient embedment of many of the wall ties in the external leaf of brickwork, as a result of incorrect construction and/or installation.”

When shown the letters and reports relating to the Dundee and Angus schools, Mr Dunlop said: “There are similarities concerning the cavity wall masonry construction.”

There was a correspondence between the Oxgangs construction problems and the issues identified in Angus and Dundee, he suggested. Many of the faults identified in Angus and Dundee schools were walls where the connectors between the inner wall of bricks and the outer wall of bricks were either missing, or not correctly embedded in the walls.

Additionally, he noted that a number of the Dundee and Angus school repairs sought to deal with “the absence of header tie restraints connecting the masonry to the steel frame”. This was another type of structural fault similar to those found in Edinburgh schools.

Asked to corroborate the council official’s assessments of the risk to school pupils, Professor Dunlop said he couldn’t be certain that there would have been no risk to pupils from the documentation he’d seen.

He said: “It is hard to confirm risk. It would depend on the height of the walls and their location, and whether they are likely to be effected by heavy wind loads and adverse weather conditions.”

“Only when the wall collapsed at Oxgangs was the risk fully realised and remedial work undertaken at 17 other schools,” he pointed out.

Government data shows that Angus council will pay a total of £199.4m for schools with a capital value of £45.7m.

The Dundee Schools PPP project will cost taxpayers a total of £397.5m for work with a capital value of £90.1m. As the chart below shows, the largest annual payments are scheduled toward the end of the contracts. The payments do not finish until 2039.

This year the private firms linked to the Dundee and Angus school PPP contracts will receive £17.4m from the two councils. Although they covered the costs of the building repairs, they will pay no further financial penalty.

The private firm that owns 100 per cent of the Angus schools PPP contract and 70 per cent of the Dundee schools PPP contract is called Elgin Infrastructure Limited. In turn this company is ultimately controlled and financed by Dalmore Capital, via a network of subsidiaries that includes a firm based in the Channel Islands.

Dalmore describes itself as an, “independent fund management company focusing on lower risk opportunities for institutional investors in the UK infrastructure sector, particularly PPP.”

The Ferret contacted Dalmore Capital for comment on the building flaws identified in the schools it has investments in. To date, the company has not responded.

The source of the problem

The Edinburgh inquiry found that the private finance “design, build and maintain” models promoted by successive Scottish governments, involved an “inevitable conflict of interest” between the various private sector contractors involved in this type of project. Ultimately, though, it concluded that private finance was not in itself to blame for the construction faults.

But Professor Dunlop disagrees and said that in his view “the real source of the problem lies within the PPP contract,” used to procure new public buildings.

He added: “This seems to be supported by the investigation carried out in Dundee on non PPP properties, where cavity wall construction was limited to games halls; extensive records were kept; a clerk of works was employed during construction and where building inspections were routinely undertaken by an in house client team, other than the contractor.

“Private finance for schools and other public projects seeks to maximise profit for the successful bidder/contractor by driving down tenders for subcontractors to the bare minimum while fast tracking the build programme; by lowering specification and design quality and reducing fees for architects and other professional services.

“With PPP the contractor is the architect’s client, not the building user and the design team has no contact with the building user. When subcontractor tenders are driven down, the subcontractor has no real incentive to complete the work to a high standard when pushed heavily for time and limited return. It is no wonder when buildings constructed under such contract conditions are found not to be fit for purpose.”

Mr Dunlop also felt that many of these issues are still relevant to private finance contracts used by the Scottish Government today.

“Although the Scottish Government’s Non Profit Distribution initiative supposedly limits the vast profits made by successful bidder during the first tranche of PPP projects, projects are still led by the successful bidder/contractor, the design team is still marginalised and has limited contact with the building user if at all, the work is still profit driven and all projects depend on the support of private finance and consequently open to construction problems, programme short-cutting and contractor abuse,” he said.

This story is part of a series, undertaken in collaboration with the Guardian, looking at private finance projects in Scotland. You can find stories by the Guardian on private finance here.